Blood Transfusion Malpractice — Deadly Delays & Hospital Errors

We refer to it as the "gift of life." We spend hundreds of millions of dollars each year in the United States to have people: donate, refrigerate, transport, process, inventory, store, and administer it. And so we take for granted that it will be available in a hospital setting should we need it as a life-saving intervention. Tragically, however, delays in providing blood transfusion, and blood transfusion errors, still claim the lives of many Americans each year. The errors that amount to medical malpractice most often involve: (1) delays in giving blood or blood products to those who urgently need them, (2) giving blood or blood products to those who do not need them, and (3) the transfusion of the wrong type of, or contaminated, blood or blood products.1

What are the Components of Blood

What are the Components of Blood

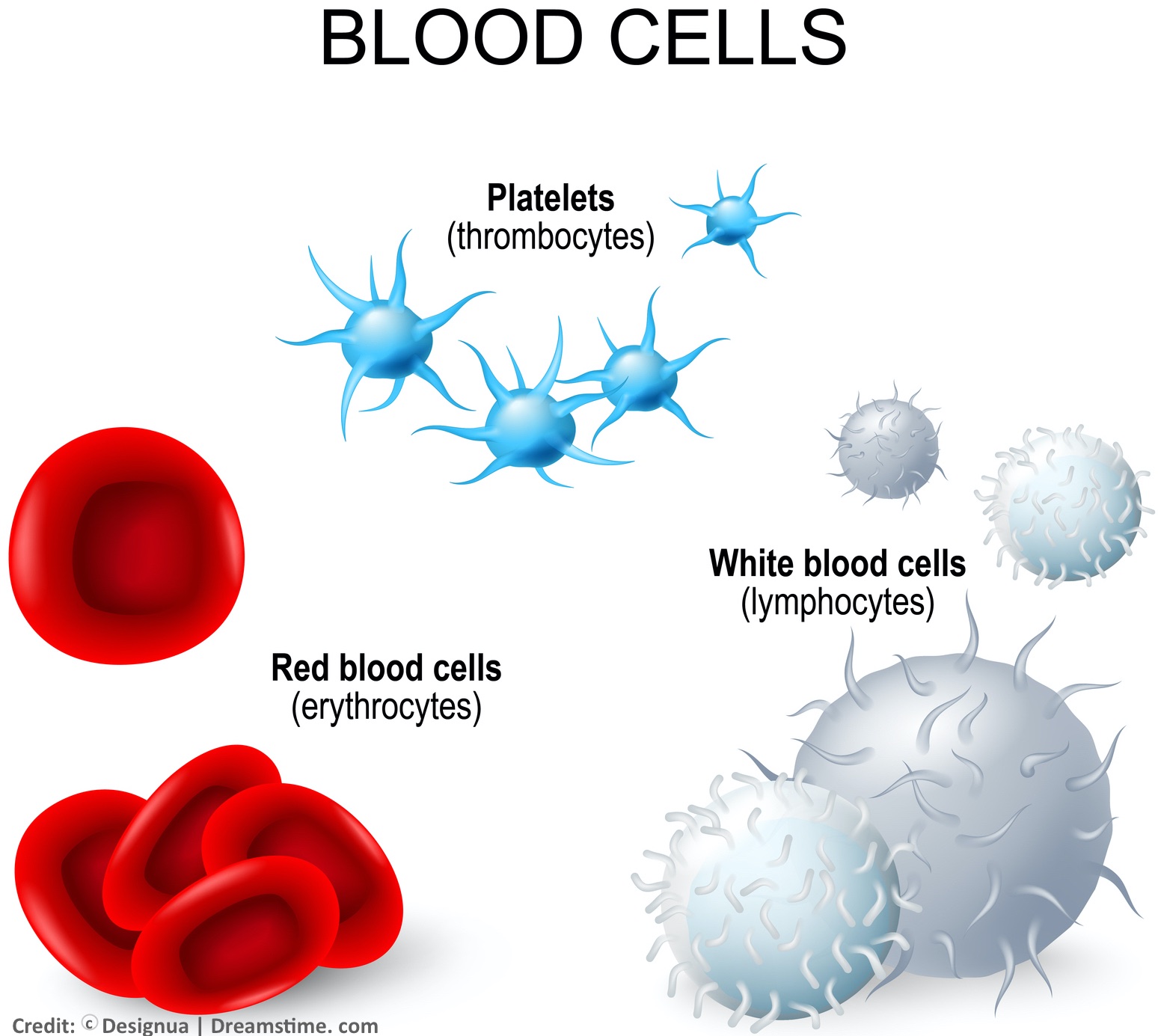

Blood consists red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, and plasma. The blood cells each have different purposes.

White blood cells (WBC) fight infection, i.e. bacteria, viruses and other foreign invaders that affect your health. So, when your WBC count is increased or elevated, it is usually because your body (bone marrow) is making more of them to fight off an infection. Platelets are involved in clotting; you can think of them as the scaffolding on which blood clots (fibrin) are formed. Red blood cells (RBC) transport oxygen through our circulation.

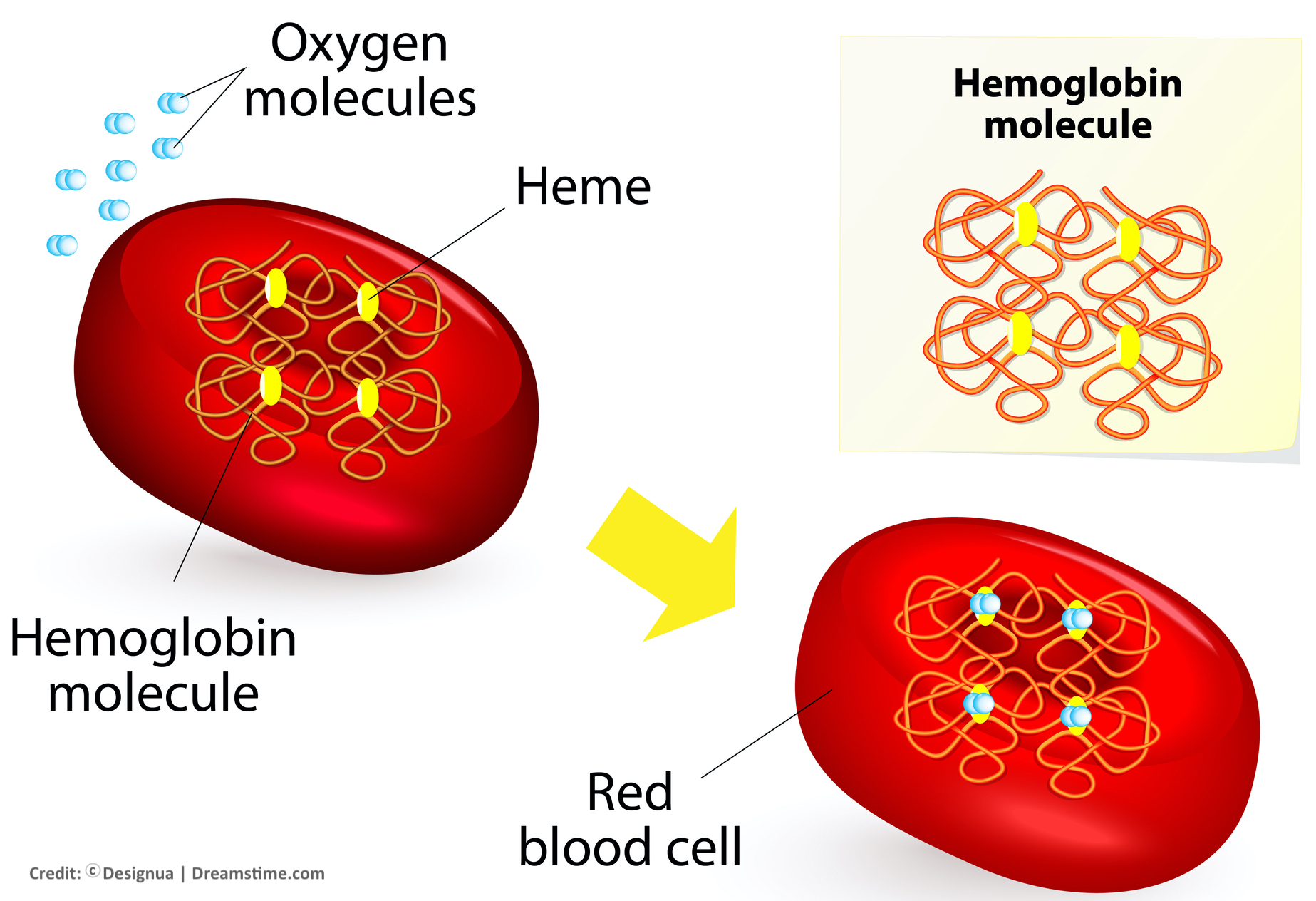

Oxygen binds in the lungs to the iron-containing protein (molecules) in RBCs called hemoglobin. Once the blood oxygen is delivered throughout our body's circulation, it becomes depleted, and the remaining carbon dioxide binds to the hemoglobin to be returned to the lungs for re-oxygenation again. If someone has less than normal amounts of RBCs or hemoglobin in their blood, then they have a condition called anemia.2

Once the blood oxygen is delivered throughout our body's circulation, it becomes depleted, and the remaining carbon dioxide binds to the hemoglobin to be returned to the lungs for re-oxygenation again. If someone has less than normal amounts of RBCs or hemoglobin in their blood, then they have a condition called anemia.2

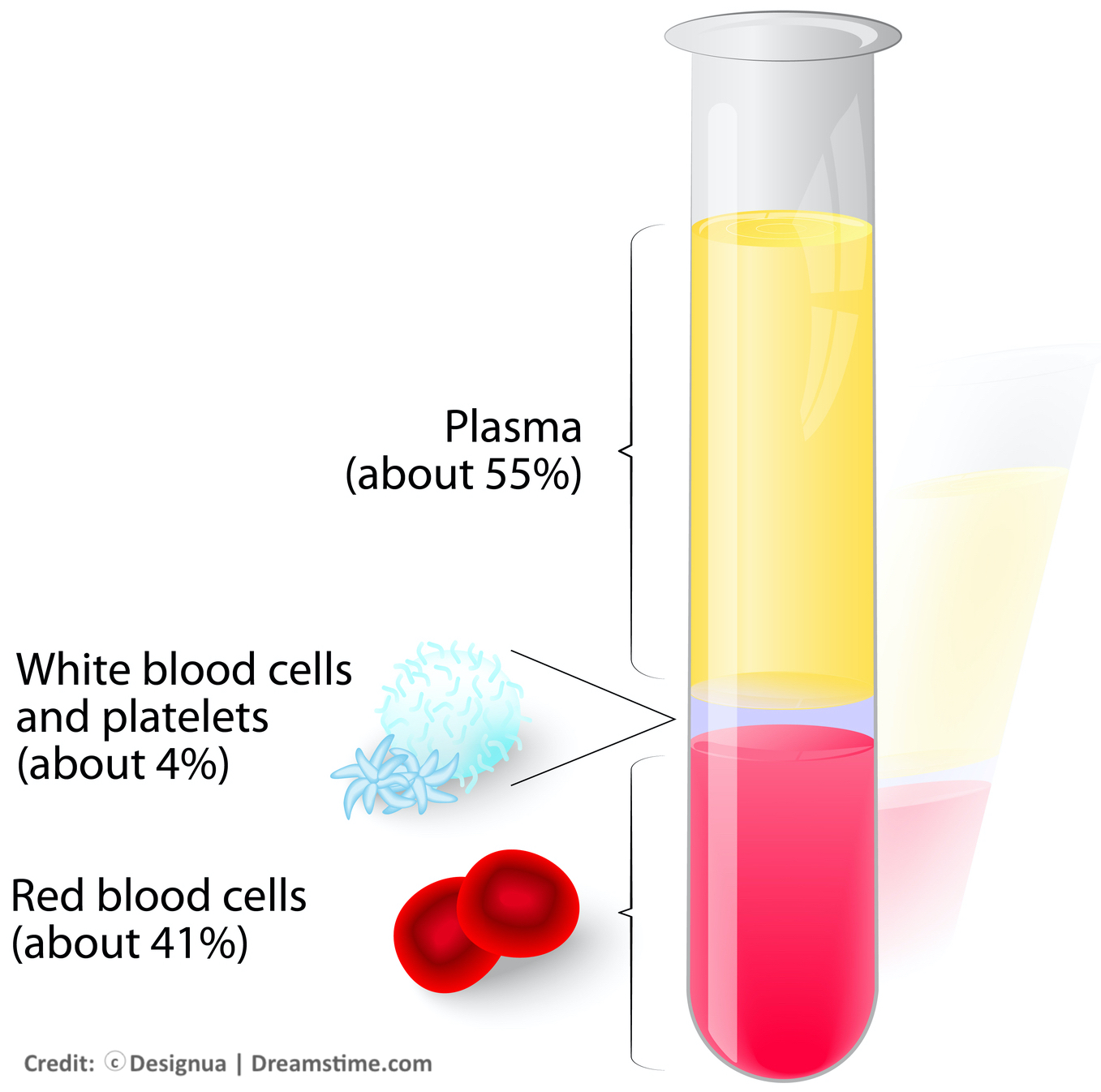

the plasma can be separated and easily seen.

the plasma can be separated and easily seen.

the plasma makes up the majority of the liquid, followed by RBCs, and then WBCs and platelets, as seen in the percentages illustrated to the left.

the plasma makes up the majority of the liquid, followed by RBCs, and then WBCs and platelets, as seen in the percentages illustrated to the left.

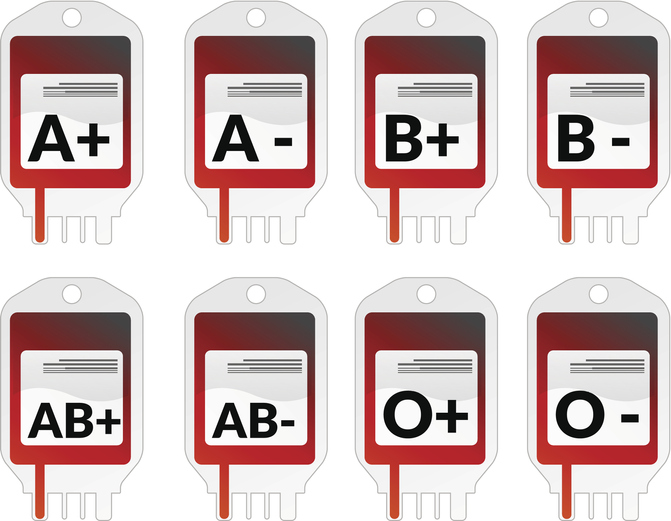

RBCs can be classified into four (4) different types, depending on whether or not they carry on their surface an A or B antigen (i.e. a substance that causes your body to produce antibodies in response to it). These 4 different blood types make up the classification that is used in order to determine what blood is compatible to be transfused.3

What are the ABO Blood Types?

The blood type system is known as ABO, representing that people have either blood type A, B, AB, or O. Each of these 4 types of red blood cells also have present or absent a protein on the surface of them, which is known as the Rh factor. If this protein is present, then you are positive for it; if it is absent, then you are said to be negative. There are eight (8) different blood type groups (with Rh factor), as seen in the illustration to the right.4

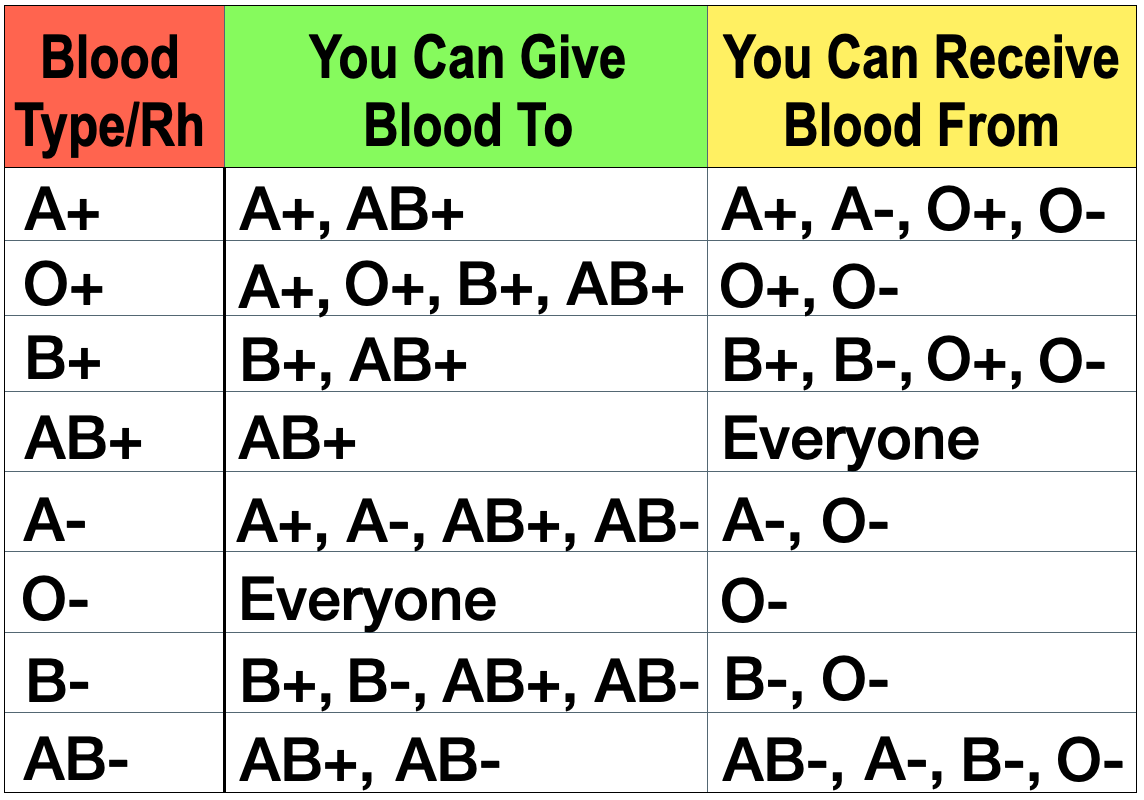

What Blood Types are Compatible for Transfusion?

If you have heard of someone being referred to as a "universal donor" blood type, this means they are type O negative and their blood can be donated to any of the 4 blood groups. If they are type AB positive, in contrast, then they are a "universal recipient" blood type—meaning they can receive blood from any of the 4 types.5

The chart below reveals the donor blood types that are compatible to be transfused into other people depending on their ABO blood type and Rh factor, as well those recipient blood types that can receive transfusions from others depending on their blood type and factor.

If an ABO/Rh incompatible blood type is mistakenly transfused into someone who is not a proper recipient for it, this is medical malpractice. This transfusion error can cause the person receiving the blood transfusion can die from what is known as a hemolytic transfusion reaction.6

What can Blood (Laboratory) Testing Reveal?

Most hospital laboratories are capable of performing many types of testing on blood. Common bloodwork testing in a hospital lab that may be considered to determine if you need a blood transfusion include the amount of hemoglobin (Hgb) and hematocrit (Hct – i.e. the volume of RBCs compared to the total blood volume), and how fast or slow your blood clots (e.g. PT, PTT, INR, fibrinogen). Additionally, these and a number of other tests can show if you have a blood disorder or condition that makes you more likely to bleed excessively–conditions such as hemophilia, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), von Willebrand disease, or clotting factor II, V, VII, X or XII deficiencies, etc.

Laboratories are also responsible for performing the ABO type testing, as well as screening of blood, to determine for whom it is compatible. Many hospitals also have their own blood banks within or as a part of the laboratory, that conducts this type of testing in advance of blood transfusion.

Crossmatch testing of other antibodies is a screening step after typing and screening which is done to determine if the intended recipient has any unexpected antibodies in the blood. The major and most important crossmatch is to make sure there is no error in the ABO type and Rh factor, which can cause the severe hemolytic transfusion reaction. This is done by comparing a small sample of the intended recipient's blood plasma with the potential donor's red blood cells.7

of other antibodies is a screening step after typing and screening which is done to determine if the intended recipient has any unexpected antibodies in the blood. The major and most important crossmatch is to make sure there is no error in the ABO type and Rh factor, which can cause the severe hemolytic transfusion reaction. This is done by comparing a small sample of the intended recipient's blood plasma with the potential donor's red blood cells.7

Minor crossmatch testing, on the other hand, looks for any antibody reaction from the potential donor's plasma against the intended recipient's red blood cells. Minor cross-matching can identify incompatible antibodies that are usually of significance in possibly causing a minor reaction—in other words, a reaction that could make the transfusion recipient sick but is usually not fatal.8

against the intended recipient's red blood cells. Minor cross-matching can identify incompatible antibodies that are usually of significance in possibly causing a minor reaction—in other words, a reaction that could make the transfusion recipient sick but is usually not fatal.8

The problem with crossmatch testing is the time needed, which can be upwards of 45 minutes to an hour when it is performed on hospital premises, at a time when the patient may be unable to wait for a transfusion.9 Moreover, with some conditions it be much more difficult achieve successful cross-matching of blood in the hospital, and so the donors' plasma/blood may need to be transported to more specialized, outside laboratory settings for more sophisticated cross-matching. This can take days, for example, and may be much longer than the patient can wait for a blood transfusion. Even then, with certain medical conditions it may be impossible to achieve blood cross-matching. This is the reason why, when time is of the essence, it may be necessary for an emergency release of blood where universal donor blood or ABO type specific (but not cross-matched or successfully cross-matched) blood is available in the lab or blood bank. The failure to release, order, or transfuse type specific or universal donor blood in an emergency can amount to medical malpractice.10

Moreover, with some conditions it be much more difficult achieve successful cross-matching of blood in the hospital, and so the donors' plasma/blood may need to be transported to more specialized, outside laboratory settings for more sophisticated cross-matching. This can take days, for example, and may be much longer than the patient can wait for a blood transfusion. Even then, with certain medical conditions it may be impossible to achieve blood cross-matching. This is the reason why, when time is of the essence, it may be necessary for an emergency release of blood where universal donor blood or ABO type specific (but not cross-matched or successfully cross-matched) blood is available in the lab or blood bank. The failure to release, order, or transfuse type specific or universal donor blood in an emergency can amount to medical malpractice.10

What are the Risks and Benefits of Blood Transfusion?

We each need a certain volume of blood with the appropriate, functioning components in order to survive. If we have too little WBCs, for instance, then we may be unable to fight off infection. If our RBCs are excessively diminished or lack sufficient iron, then we may not be able to get adequate oxygen transported via the blood to our organs and tissues, a condition known as hypoxia. If we have too little of the other blood products, i.e. platelets and/or plasma, then we may bleed excessively. And of course we need enough blood as a whole so that our heart has a sufficient volume to pump through it instead of collapsing—kind of like an engine needs enough oil so as not to seize up. So, the benefits of blood or blood products transfusions are self-evident to those who urgently need them: they can be life-saving.

On the other hand, there are always risks with transfusion of blood or blood products. Although the risks are extremely rare that someone will have a lethal reaction or receive a transmitted disease that could be fatal, these things still happen each year.11 Furthermore, blood transfusion can result in a couple of other very rare but sometimes fatal disorders where the lungs are injured or the circulation is overloaded. These conditions and disorders can occur due to improper testing or transfusions, but also when proper precautions are followed.12

Why do Deadly Delays of Blood Transfusions Occur?

The adult human body contains, on average, more than 5 liters (6 quarts) of blood. When significant or massive blood loss occurs, there are various stages that a person often goes through, depending on the severity, in terms of their: blood pressure decreasing, pulse pressure narrowing, breathing rate increasing, and mental status changing from anxious to confused, or ultimately to lethargic (sluggish) or unresponsive.13 These clinical changes of hemorrhagic shock from low blood volume (hypovolemia) must be quickly recognized. For a patient with severe, acute, hemorrhage or a bleeding disorder, time may be critical in restoring blood volume to the body in an amount sufficient to keep the heart pumping, and the organs and tissues perfused with oxygenated blood. These are commonly situations involving: trauma victims, mothers following childbirth, people with acute bleeding or clotting disorders, etc. Intravenous fluids (crystalloids) and medications (volume expanders) are usually given to these patients as first line treatments–to provide some liquid volume so the heart can pump, and so as to prevent it from collapsing. Tragically, however, sometimes this practice does not occur timely, or even when it does the patient may not thereafter receive timely blood transfusion.

It must be remembered that when fluids are given to replace the loss of blood, the fluids do not contain hemoglobin (and thus oxygen-carrying capacity) like blood. So, even though the patient with severe bleeding may be administered enough fluid for the heart to pump, that fluid dilutes the blood and if the patient doesn't receive a timely blood transfusion he or she can still die or suffer severe brain/organ injury from the severe lack of oxygen in the blood (hypoxia) and continued bleeding.

There are numerous reasons that blood transfusions are excessively delayed due to medical malpractice. These delays can result in death or brain injury from hemorrhagic shock. While there is no single blood test result that may trigger the doctor to order a blood transfusion, many institutions and authorities use a range of decreased Hgb and/or Hct levels as guidelines for when to order transfusion.14 Additionally, doctors use the patient's presentation (clinical condition) to determine when and how quickly a blood transfusion is needed.15 Excessive delays of blood transfusion in cases of hemorrhagic (hypovolemic) shock can relate to the negligent failures of health care providers to properly or timely:

- Estimate blood loss, either visually or by testing results

- Order blood testing, or to order it on an immediate (stat) basis

- Obtain, learn, or know the limitations of the blood test results

- Recognized the degree or rapidity of hemorrhagic shock

- Stay ahead of the need for fluid and/or blood volume

- Obtain and/or transport the blood or blood products

- Have a sufficient inventory of blood or blood products

- Recognize the critical need for acute blood volume despite crossmatch concerns

- Order or transfuse universal donor (type O) blood in an emergency

- Order or transfuse necessary blood products

Death from lack of blood transfusion in emergency situations is known to result each year in the United States in situations where these type of human (healthcare provider) errors occur, and also from situations where people refuse blood transfusion, such as for religious or other reasons.16

Why do Deadly Conditions Occur Due to Unnecessary Blood Transfusions?

On the other hand, there are many situations in which blood transfusion is not really needed but doctors order them anyway.17 Most of the time there will be no harm. But what if a patient develops a rare but fatal reaction to an unnecessary blood or blood product transfusion? If this occurs, then it is another situation where medical malpractice may exist.

There are two potentially fatal conditions that can and do occur, albeit very rarely, from blood or blood product transfusion even when appropriate testing and transfusion practices are followed. The first is transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) and the second is transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO).18 With TRALI and TACO, a patient may have a hypersensitivity to the blood or blood products that causes fluid in the lungs and heart dysfunction; this can be due to patient factors (e.g. elderly, other serious health conditions) or from the nature (and possibly age) of the blood or blood products transfused (TRALI) or the rate and volume of the transfusion (TACO).19

The first is transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) and the second is transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO).18 With TRALI and TACO, a patient may have a hypersensitivity to the blood or blood products that causes fluid in the lungs and heart dysfunction; this can be due to patient factors (e.g. elderly, other serious health conditions) or from the nature (and possibly age) of the blood or blood products transfused (TRALI) or the rate and volume of the transfusion (TACO).19

The risks of these conditions, as mentioned, is very rare and, therefore, almost always outweighed by the need for blood transfusion in situations where the transfusion is urgently required to save a patient's life. Yet no patient should die or be injured for any reason associated with an unnecessary blood or blood product transfusion.

Why do Deadly Reactions or Infections Occur from Improper Blood Transfusions?

Likewise, medical, nursing and laboratory/blood bank errors still occur in U.S. hospitals each year. Again these are rare situations, but they inevitably occur due to human error or carelessness; in other words, medical malpractice. Most of these situations occur result from properly labeled blood that is transfused into an unintended recipient, or from improperly labeled (or mislabeled) blood or blood products. And when these types of errors occur, as little as 30 cc/ml (about 2 tablespoons) of incompatible blood can be fatal.20

The reactions that make up these errors are the major incompatibility ones, known as hemolytic transfusion reactions (HTR). About 2/3 of the time HTRs are due to incompatible ABO transfusions. HTRs can either occur soon or acutely after the transfusion, or they can be delayed. The acute HTRs are more commonly lethal than the delayed ones. With an HTR, the recipients' antibodies destroy the donor's blood cells or products because the recipient's immune system treats them as foreign invaders. An acute HTR is a medical emergency, and a patient may initially develop nausea, vomiting, fever, chills, low blood pressure, kidney failure, and DIC—which can destroy more blood cells and products in the body and create an irreversible cascade of unrelenting hemorrhage.21

The reactions that make up these errors are the major incompatibility ones, known as hemolytic transfusion reactions (HTR). About 2/3 of the time HTRs are due to incompatible ABO transfusions. HTRs can either occur soon or acutely after the transfusion, or they can be delayed. The acute HTRs are more commonly lethal than the delayed ones. With an HTR, the recipients' antibodies destroy the donor's blood cells or products because the recipient's immune system treats them as foreign invaders. An acute HTR is a medical emergency, and a patient may initially develop nausea, vomiting, fever, chills, low blood pressure, kidney failure, and DIC—which can destroy more blood cells and products in the body and create an irreversible cascade of unrelenting hemorrhage.21

The most common negligent conduct responsible for HTRs, in addition to blood or blood products being given to the wrong recipient or being incorrectly labeled, are that blood is collected from the wrong patient or is misidentified or improperly issued from the laboratory or blood bank. Once again, these are instances where there may be medical malpractice.

The factors that contribute to these negligent healthcare errors are the following failures to:22

- Follow standard procedures

- Use specific (instead of preprinted sample) labels

- Distinguish between similar or identical patient names

- Perform testing or issuance of blood or blood products on a stat basis

- Process specimens from more than one patient simultaneously

- Recognize computer error messages (and overriding them)

- Segregate sufficient units of blood or blood products in refrigerators

In addition to HTRs, life-threatening infection can also be transmitted with blood transfusion, and although this is also rare it can likewise result in death. Transfusion-associated sepsis (TAS) or other infectious conditions have been recognized with various organisms, including those that are bacterial (e.g. staph, strep, other), viral (e.g. Zika, West Nile, HIV, Hepatitis, other), parasitic (e.g. malaria, Chagas' disease) and prion-related (i.e. Creutzfeldt-Jakob).23 TAS or transmitted infections sometimes occur from improper screening at outside facilities but certain transmitted infections or TAS may occur at times with substandard care in a hospital setting as well.

The Lawyer's Role

The lawyer who is experienced in handling medical malpractice cases involving delays and errors with transfusion of blood and blood products will know and understand the medicine and authoritative medical literature on these subjects. He or she will be able to work with qualified hematologists, pathologist, laboratory and blood bank personnel and other expert witnesses to determine how and why a someone died or experienced organ/brain injury, as well as if it whether or not this tragedy occurred due to negligence or medical malpractice involving delays or errors concerning blood transfusion.

Contact Us

The attorneys at Clore Law Group have significant experience and expertise with successfully handling death and serious injury medical malpractice cases related to delay in, and errors involving blood and blood product transfusions. We have handled such cases where death has occurred due to transfusion delays in cases of bleeding (hemorrhage) following childbirth, as well as from other conditions including acute anemias and blood disorders. We have also prosecuted such cases of death and serious injury where improper blood/product contamination has occurred, including where lethal infections occurred as a result. If a loved one or family member experienced death or a severe injury in connection with a blood or blood product transfusion error or delay, you can email us at [email protected], or call us Toll-Free at 1-800-610-2546 for a free and confidential consultation.

Sources

- The actual incidence of fatalities due transfusions that are inappropriately delayed or are not given is unknown. However, the most common cause of death in trauma victims is shock from bleeding (hemorrhage). See Smith CE, Bauer AM, et al, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), Committee on Blood Management (COBM), Massive Transfusion Protocol for Hemorrhagic Shock, Introductory Comments, pp. 1-11, at 1 (2011). In the U.S., over 60,000 patients are estimated each year to die from hemorrhagic shock, and a great deal of work is needed for early recognition and reduction of death, including with blood transfusion, due to this condition. Cannon JW, Hemorrhagic Shock, N Eng J Med. Vol 378, No. 4, pp. 370-79 (Jan. 24, 2018). With respect to transfusion errors, however, the statistics are documented. The fatalities from transfusion errors, reported to the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA), amount at least 30-50 people annually, as seen from the statistics from 2009 through 2016. See Fatalities Reported to FDA Following Blood Collection and Transfusion, Annual Summaries.

- See, e.g., Dean L, Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens, National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, U.S. 2005).

- Id.; see also, e.g., Transfusion Medicine, Lab Tests Online, at: https://labtestsonline.org/articles/transfusion-medicine.

- Id.: see also, e.g., https://www.redcrossblood.org/donate-blood/blood-types.html.

- Id. at: https://www.redcrossblood.org/donate-blood/blood-types.html?icid=rdrt-blood-types&imed=direct&isource=redirect.

- The term “hemolytic” refers to destruction red blood cells, which is what happens to the donor’s red blood cells when the wrong ABO type are infused into someone with an incompatible type—i.e. the recipient’s antibodies destroy or rupture the donor’s RBCs, thereby allowing the hemoglobin to leak into vascular (blood vessels) system, and the excess hemoglobin can damage the kidneys, liver and result in shock and further bleeding from a condition known as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). If only the Rh factor of the wrong type is transfused, i.e. either the positive or negative factor is in error but not the ABO type, then the hemolytic or hemolysis reaction process usually results in the destruction of donor RBCs in the recipient’s liver or spleen, and is sometimes more treatable, but can still be fatal. There are also other types non-hemolytic reactions, including allergic or hypersensitivity type reactions, that can occur from blood or blood product transfusion, and these reactions can result in fever and illness but are usually non-fatal. See Strobel E, Hemolytic Transfusion Reactions, Transfus Med Hemother. Vol. 35, No. 5, pp. 346-53 (Sep. 18, 2008); Harewood J, Master SR, Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction, NCBI Bookshelf, National Institutes of Health (NIH 2018), at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448158/, and Ringhauser H, Cipolla J, Wrong Blood Type: Transfusion Reaction, Ch. 9 (InTech 2017).

- See Transfusion Medicine, Lab Tests Online, n3; Cross-Matching: Types, Purpose, Principle, Procedure and Interpretation, Hematol, Immunol. pp. 1-9 (June 21, 2015), at: https://laboratoryinfo.com/cross-matching/; and Whitlock J, Understanding Common Blood Tests and What They Mean, verywellhealth pp. 1-5 (Aug. 30, 2018), at:

https://www.verywellhealth.com/understanding-common-blood-tests-and-what-they-mean-3156935. - See Cross-Matching: Types, Purpose, Principle, Procedure and Interpretation, n7; Dean L, Blood Transfusions and the immune system, Ch. 3, pp. 1-8, NCBI Bookshelf, NIH: National Center for Biotechnology Information (2005); and BloodBankGuy, Minor Crossmatch, at: https://www.bbguy.org/education/glossary/glm09/.

- See, e.g., Cross-Matching: Types, Purpose, Principle, Procedure and Interpretation, n7.

- See, e.g., Weinstein R, Red Blood Cell Transfusion: A Pocket Guide for the Clinician, pp. 1-4, Am Soc Hematol. (Nov. 2016); Transfusion Medicine, Lab Tests Online, n3, at 9; and Ness P, How do I encourage clinicians to transfuse mismatched blood to patients with autoimmune hemolytic anemia in urgent situations?, Transfus. Vol. 46, No. 11, pp. 1859-62 (Dec. 2006).

- See Fatalities Reported to FDA Following Blood Collection and Transfusion, Annual Summaries, n1.

- See, e.g., Roubinian N, Murphy E, Transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO): prevention, management, and patient outcomes, Review (DovePress 2015), at: https://www.dovepress.com/transfusion-associated-circulatory-overload-taco-prevention-management-peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-IJCTM.

- See, e.g., Cannon JW, Hemorrhagic Shock, n1 (noting at p. 375, Table 2, the American College of Surgeons (ACOS) Committee on Trauma, Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) Student Course Manual, “Classification of Hemorrhagic Shock” (9th ed. 2012)). See also Dean L, Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens, National Center for Biotechnology Information, n.2.

- See, e.g., NIH Consensus Conference. Perioperative Red Blood Cell Transfusions, JAMA Vol. 260, No. 18, p. 2700 (1988); Myhre BA, The Transfusion Trigger—The Search for a Quantitative Holy Grail, Ann Clin Lab Sci. Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 359-64 (Fall 2001); Gutierrez G, Reines HD, Clinical Review: Hemorrhagic Shock, Crit. Care Vol. 8, No. 5, pp. 373-81 (2004); and, Ansari S, Szallasi A, Blood management by transfusion triggers: when less is more, Blood Tranfus. Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 28-33 (Jan. 2012).

- Id.

- See Fatalities Reported to FDA Following Blood Collection and Transfusion, Annual Summaries, n1; Rogers DM, Crookston KP, The approach to the patient who refuses blood transfusion, Trasfus. Vol. 46, No. 9, p. 1471 (2006). See also Chand NK, Subramanya HB, Management of patients who refuse blood transfusion, Ind J Anaesth. Vol. 58, No. 5, pp. 658-64 (Sep.-Oct. 2014).

- See, e.g., Ward B, Joint Commission: Half of blood transfusions are unnecessary and cost millions, Accred & Qual. Advisor (Jul. 28, 2017), at: http://blogs.hcpro.com/acc/2017/07/joint-commission-half-of-blood-transfusions-are-unnecessary-and-cost-millions/.

- See, e.g., Roubinian N, Murphy E, Transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO): prevention, management, and patient outcomes, n12; Silliman CC, Ambruso DR, Transfusion-related acute lung injury, Blood Vol. 105, pp. 2266-2273 (2005); and, Fatalities Reported to FDA Following Blood Collection and Transfusion, Annual Summaries, n1, at 4-10.

- Id.; see also Koch CG, Li L, et al, Duration of red-cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery, N Engl J Med. Vol. 358, pp. 1229–1239 (2008).

- Strong M, Hemolytic Transfusion Reactions, Part 1: Biological Product Deviations (Errors and Accidents), Blood Bulletin, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 1-2 (America’s Blood Centers 2000).

- Id.; Strobel E, Hemolytic Transfusion Reactions, n6; and, Harewood J, Master SR, Hemolytic Transfusion Reaction, n6.

- Strong M, Hemolytic Transfusion Reactions, Part 1: Biological Product Deviations (Errors and Accidents), at 2.

- See, e.g., Vamvakas EC, Blajchman MA, Transfusion-related mortality: the ongoing risks of allogenic blood transfusion and the available strategies for their prevention, Blood Vol. 113, pp. 3406-17 (2009); Fatalities Reported to FDA Following Blood Collection and Transfusion, Annual Summaries, n1, at 10-13; Dodd RY, Transmission of Parasites by Blood Transfusion, Vox Sang. Vol. 74, Suppl. 2, pp. 161-63 (1998).