Drug and Medication Errors

Drug and medication1 errors that occur in the health care setting are considered "never events"--meaning they should never happen.2 Yet not only do they happen, these errors account for at least 1.5 million adverse patient health events each year in the U.S. Adverse drug events (ADEs) are estimated to kill 173,000 Americans annually, with 73,000 cases related to opioids alone.3

What Constitutes a Medication Error?

The Institute of Medicine defines an "error" as "the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended (error of execution) or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim (error of planning). An error may be an act of commission or an act of omission."4 So, medication errors refer to situations in which the patient receives the medication differently than intended by the doctor/prescriber. Medication errors are commonly defined in the U.S. to mean:

"Any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the healthcare professional, patient, or consumer. Such events may be related to professional practice, health care products, procedures, and systems, including prescribing, order communication, product labeling, packaging, and nomenclature, compounding, dispensing, distribution, administration, education, monitoring, and use."5

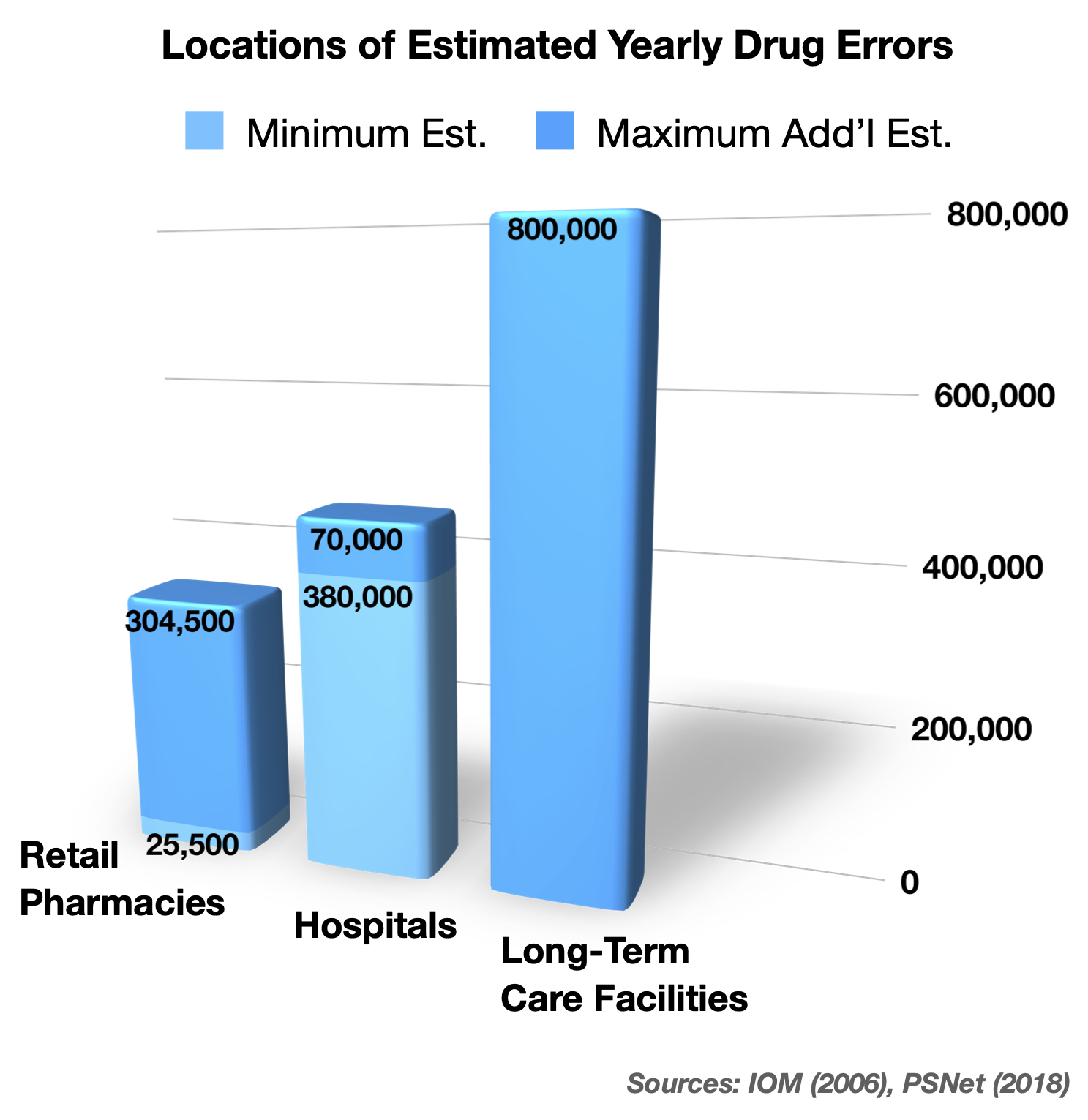

When and Where Do Medication Errors Occur?

Drug errors happen most frequently at/in community (retail) pharmacies, hospitals, and long-term care facilities such as nursing homes. And they occur at all of the foregoing steps of the medication process, but they are most frequent at the prescribing (doctor ordering) and administering stages.6 Health care providers are taught to observe the "5 rights" when administering drugs7:

- Right patient

- Right drug

- Right dose

- Right route

- Right time

Medication errors often occur when one of these "rights" is not followed‚ in other words, when the "wrong" patient, drug, dose, route or time is selected.

Why Do Medication Errors Happen?

Medication errors are invariably due to human error. Since they frequently happen at every stage of the process, they are caused by physicians who prescribe/order them, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians who assist in this process as well as who compound, fill and dispense them, and nurses who ultimately administer them. There are many causes of these errors, including these common ones:

1. Doctor Prescribing/Ordering:

- the wrong drug, dose, or route in view of the patient's age or other health conditions

- drugs which are contraindicated because of other medications the patient is taking

- certain drugs without doing necessary bloodwork on the patient before or during

- with verbal or telephone orders when time is not of the essence

- when changing a drug route, i.e. IV to oral, and using the wrong conversion formula

- with unclear handwriting or prescription errors, including in computer order entry

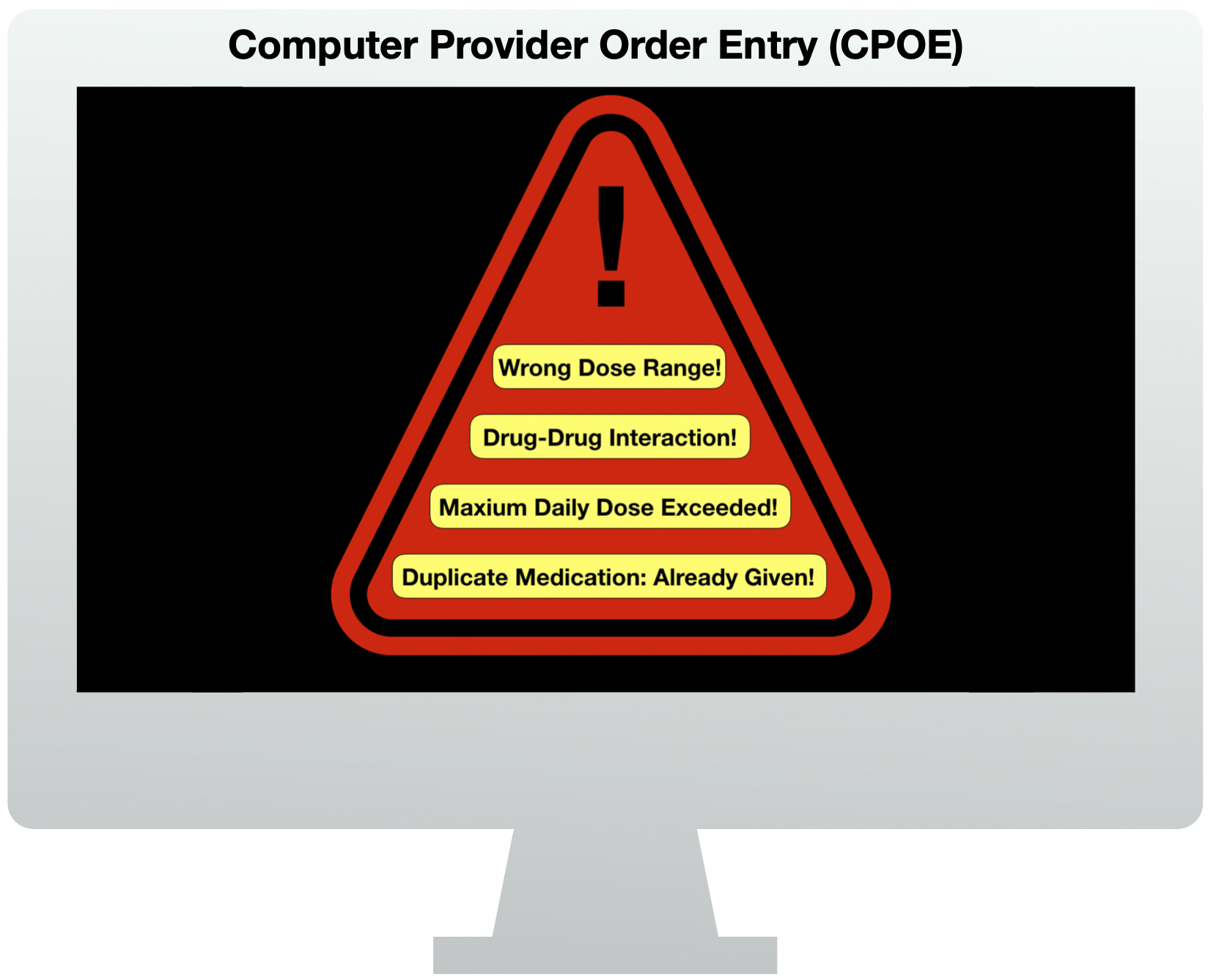

- by overriding computer provider order entry (CPOE) alerts and warnings

- without clear communication to the patient about adverse signs/symptoms to watch for.

2. Pharmacy, Pharmacists and Technicians Filling/Dispensing:

- without doing a reconciliation of the patient's current medications

- in transcribing/typing physician verbal/telephone order without proper order read-back

- by failing to take into account the patient's age, weight, or kidney/liver conditions

- by not recognizing a dose, drug conversion, or route is excessive for the patient

- by failing to seek clarification from the physician for unclear orders

- by dispensing the wrong medication, or an excessive dose, strength or quantity

- by failing to properly verify the correct drug, dose, route, or time

- by failing to have a second pharmacist review orders for high-risk drugs or children.

- also by overriding CPOE alerts and warnings.

3. Nursing Administration:

- by failing to use, follow, and verify the 5 R's

- in transcribing/typing physician verbal/telephone order without proper order read-back

- by mistaking similarities in drug names or abbreviations

- by not recognizing a dose, drug conversion, or route is excessive for the patient

- by failing to seek clarification from the physician for unclear orders

- by failing to properly verify the order and the correct drug, dose, route, or time

- in the case of IV drugs, by improper tube connections or drip/pump settings

- by failing to monitor the patient and any IV drug equipment.

What are the Most Common Types of Medication Errors and the Drugs Implicated?

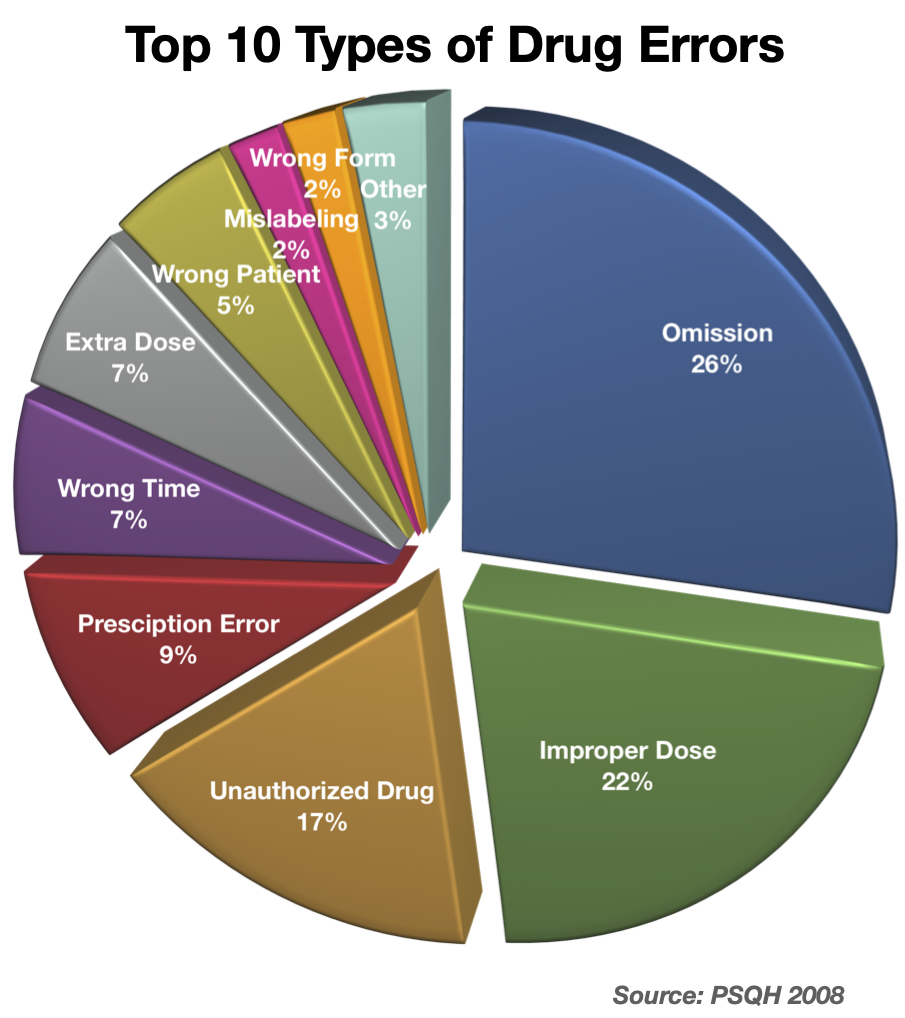

According to a study from 2006-2008, the 10 primary reasons for, and types of, drug errors were due to the situations seen in the pie chart to the right. The same study revealed that insulin, blood thinners, heart medications, antihistamines and decongestants, and opioids were most commonly implicated high-risk drugs. Specifically, these drugs were responsible for the following percentages of drug erro

- Insulin – 39%

- Heparin – 27%

- Warfarin – 22%

- Digoxin – 6%

- Promethazine – 1%

- Others – 5%

What are the Underlying Reasons for Medication Errors?

The World Health Organization (WHO) lists many reasons that the foregoing human errors occur. The factors or characteristics concern all of the foregoing types of health care providers: lack of knowledge about the drug or patient's condition, lack of training, inadequate perception of the risk to the patient, overworked or fatigued health care workers, and poor communication between health care professionals and patients. Additionally, the WHO lists other contributing factors as those associated with work (e.g. workload and time pressures, distractions and interruptions, lack of standardized protocols, and insufficient resources), medicines (e.g. mis-naming, mislabeling, and mis-packaging), and tasks and systems (e.g. repetition, patient monitoring, inadequate CPOE design, etc.).9

Who are the People Most at Risk for Medication Errors?

All drugs have side effects. The extent to which side effects or complications can occur depends a lot on the type of drug given, the amount, timing, frequency and route of drug administration, and the patient's age, weight, preexisting conditions, current drug regimen, and allergies. Children, the elderly, and people with preexisting conditions like kidney or liver disease, or sleep apnea, are at greatest risk from medication errors. With regard to infants and children, they at great risk from improper dosing errors due to their small size and weight as compared to adults, especially from high-risk medications such as strong pain relievers, opioids, and narcotics. The elderly are also at increased risk because they often have other preexisting conditions such as heart, lung, kidney or liver disease which may make a therapeutic drug course become more dangerous for them; their bodies may not eliminate drugs as well, and they may be more susceptible to build-up of drugs in their system and more vulnerable to organ/system affects. The elderly are also more susceptible to medication errors because they are usually taking multiple prescription medications already. So, they are vulnerable to drug-drug interactions.10 By the same token, people with underlying kidney or liver disease are often at much greater risk, because the liver breaks down many or most drugs into metabolites, and the kidneys excrete these drug metabolites from the body. If the liver does not break down drugs sufficiently (metabolize), the person can be at increased risk of the side effects.  Likewise, if the drug metabolites build up (accumulate) in the body--such as in the case of diabetics with chronic kidney disease--then these metabolites can also cause harmful side effects. This is particularly true with opioids and narcotic drugs, since the metabolites of these drugs can have the same side effects as the drug itself. Too much can affect breathing, and cause the lungs to quit working (respiratory depression or failure), or cause electrical disturbances in the rhythm of the heart (arrhythmia). This means that even though an opioid may be proper in one adult without kidney disease, it can cause an overdose or be lethal in another adult patient with that disease. As a consequence, doctors and pharmacists also have to consider bloodwork and test results such as creatinine clearance, to know if someone's kidneys will "clear" the drug adequately. If not, then dosing reductions are necessary.11 Likewise, people with sleep apnea are already prone to having brief periods where they stop breathing during sleep; they can have a worsening of this process with opioids/narcotics, whereby they are not breathing for too long. In all of these circumstances, the lungs and heart can fail, and death or brain damage from lack of oxygen can occur. Additionally, some drugs have a very narrow window between how much is therapeutic, i.e. proper for treatment, and how much is excessive, i.e. toxic to the body. This is called a "narrow therapeutic index" or NTI. An NTI is common with many narcotics and opioids, and since doctors don't necessarily know how someone will react to a medication beforehand, great care in opioid selection, dosing, and monitoring is necessary. Once again, this means dosing reductions based on patient risks, and increased patient monitoring (for side effects) may be required, to identify heart, lungs or breathing problems before they reach the point of no return. Sometimes the administration of a drug antidote is also necessary‚ such as Narcan (naloxone) which is given for opioid overdoses. To appreciate all these concerns, doctors, pharmacists and nurses have to understand basic pharmacology (uses, effects and actions of drugs) of medications they order, dispense and administer. This requires an understanding of what the body does to drugs (pharmacokinetics) and what effects drugs have on the body (pharmacodynamics). Health care providers should have a satisfactory understanding of a drug before they order or give it to a patient. If they don't, they can quickly and easily learn about drug interactions, side effects, manufacturer recommendations, warnings, and complications from numerous available sources at their hospital, facilities, or simply online at the time they are considering a particular drug for a patient.

Likewise, if the drug metabolites build up (accumulate) in the body--such as in the case of diabetics with chronic kidney disease--then these metabolites can also cause harmful side effects. This is particularly true with opioids and narcotic drugs, since the metabolites of these drugs can have the same side effects as the drug itself. Too much can affect breathing, and cause the lungs to quit working (respiratory depression or failure), or cause electrical disturbances in the rhythm of the heart (arrhythmia). This means that even though an opioid may be proper in one adult without kidney disease, it can cause an overdose or be lethal in another adult patient with that disease. As a consequence, doctors and pharmacists also have to consider bloodwork and test results such as creatinine clearance, to know if someone's kidneys will "clear" the drug adequately. If not, then dosing reductions are necessary.11 Likewise, people with sleep apnea are already prone to having brief periods where they stop breathing during sleep; they can have a worsening of this process with opioids/narcotics, whereby they are not breathing for too long. In all of these circumstances, the lungs and heart can fail, and death or brain damage from lack of oxygen can occur. Additionally, some drugs have a very narrow window between how much is therapeutic, i.e. proper for treatment, and how much is excessive, i.e. toxic to the body. This is called a "narrow therapeutic index" or NTI. An NTI is common with many narcotics and opioids, and since doctors don't necessarily know how someone will react to a medication beforehand, great care in opioid selection, dosing, and monitoring is necessary. Once again, this means dosing reductions based on patient risks, and increased patient monitoring (for side effects) may be required, to identify heart, lungs or breathing problems before they reach the point of no return. Sometimes the administration of a drug antidote is also necessary‚ such as Narcan (naloxone) which is given for opioid overdoses. To appreciate all these concerns, doctors, pharmacists and nurses have to understand basic pharmacology (uses, effects and actions of drugs) of medications they order, dispense and administer. This requires an understanding of what the body does to drugs (pharmacokinetics) and what effects drugs have on the body (pharmacodynamics). Health care providers should have a satisfactory understanding of a drug before they order or give it to a patient. If they don't, they can quickly and easily learn about drug interactions, side effects, manufacturer recommendations, warnings, and complications from numerous available sources at their hospital, facilities, or simply online at the time they are considering a particular drug for a patient.

Is a Lawsuit Necessary?

Just because drug errors should never happen does not mean that a healthcare institution or provider will admit that it occurred due to their negligence or malpractice, or that they will settle for a fair or reasonable amount. In fact, healthcare facilities, providers, and their attorneys usually deny responsibility in court, and claim that the error did not amount to negligence and/or did not cause any serious or permanent injury. As a result, civil lawsuits for medical malpractice (negligence) are typically the only way to seek accountability and justice.

Contact Us

The lawyer who is experienced in handling drug or medication error cases will know and understand these subjects and the important pharmacological and medical information. He or she will be able to work with qualified expert witnesses in the field(s) of pharmacy, medicine, and often toxicology to determine and prove how and why it occurred, and how it should have been prevented. The attorneys at Clore Law Group have significant experience and expertise with handling drug and medication error cases to successful resolution. We have successfully prosecuted many cases of drug errors, including those involving:

- retail pharmacy drug errors

- physician drug prescribing errors

- hospital pharmacy/pharmacist drug errors

- nursing administration drug errors

- errors in healthcare CPOE system training and education

- drug overdoses, miscalculation of drug conversions, excessive dosing

- failure to timely give antidotes

- IV pump/drip calculations, settings, and tubing connection errors

- antibiotic, opioid, narcotic, drug allergy, and other medication errors

- failure to order proper testing for patients prior to and during drug prescribing

- improper drug selection and dosing due to patient conditions and age.

If you or a loved one experienced a drug or medication error, you can email us at [email protected], or call us Toll-Free at 1-800-610-2546 for a free and confidential consultation.

Sources

- The traditional distinction between a medicine and a drug is that the former is used to prevent, alleviate, or cure a disease, condition or ailment; whereas, not all drugs have curative properties. For instance, pain-relieving drugs are used to take away or alleviate pain, not to cure. So, while all medications include drugs, all drugs (including illegal ones) are not medicines. The FDA basically considers drugs and legally recognized medications to be the same, by defining a drug as “a substance recognized by an official pharmacopeia [pharmacy publication] or formulary [official list of medicines]” or “a substance intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of a disease.” See https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=glossary.page.

- See Never Events, Patient Safety Network (PSNet), Sep. 2019 at https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/never-events. See also the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Newsroom Fact Sheet, Eliminating Serious, Preventable, and Costly Medical Errors – Never Events, p. 1, May 18, 2006, citing the NQF: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/eliminating-serious-preventable-and-costly-medical-errors-never-events.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM), Preventing Medication Errors, Report Brief, p. 1, (Inst of Med of the Nat’l Acad. July 2006).

- IOM, Patient Safety, Achieving a New Standard of Care (Wash. DC, Nat Acad. Press 2004).

- National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCCMERP), at: https://www.nccmerp.org/about-medication-errors.

- IOM, Preventing Medication Errors, fn. 3; Patient Safety Network, Safety in the Retail Pharmacy, Oct. 1, 2018, at: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/perspective/safety-retail-pharmacy.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), The Five Rights of Medication Administration, at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/ImprovementStories/FiveRightsofMedicationAdministration.aspx.

- Rashidee A, Hart J, Data Trends: High-Alert Medications: Error Prevalence and Severity, Patient Safety & Quality Healthcare (PSQH) July 14, 2009.

- World Health Organization (WHO), Medication Errors: Technical Series on Safer Primary Care, pp. 7-8 (WHO 2016), at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/252274/9789241511643-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- See, e.g., Thomas AN, Belser D, et al, Wrong Patient, Wrong Drug: An Unfortunate Confluence of Events – Vignettes in Patient Safety, Vol. 1, Firstenberg MS, Stawicki SP, Intech Open (Sep. 13, 2017), available online at: https://www.intechopen.com/books/vignettes-in-patient-safety-volume-1/wrong-patient-wrong-drug-an-unfortunate-confluence-of-events.

- See, e.g., Launay-Vacher V, Svetlana K, et al, Treatment of Pain in Patients with Renal Insufficiency: The World Health Organization Three-Step Ladder Adapted, Vol. 6, No. 3, J. Pain, pp. 137-148 (Mar. 2005).