Beware the Common Bile Duct: Surgical Malpractice in Gallbladder Operations

Gallstone disease can be traced to ancient times. The first surgical procedure to remove gallstones is reported to have occurred in 1618, and until the late 1800's these operations were primarily performed by opening the abdominal wall and making a hole in the gallbladder for drainage and gallstone removal, a procedure known as cholecystostomy. In 1891, the first gallbladder removal surgery (called cholecystectomy) was performed. Unlike a cholecystostomy, removing the gallbladder during these times was associated with inadvertent surgeon-caused (i.e. iatrogenic) injury, including injury to the common bile duct, first described in 1891.1 Fast-forward over a century later and, despite all the technological wonders of our time, "[i]atrogenic bile duct injuries (IBDI) remain an important problem in gastrointestinal surgery."2 These serious injuries are commonly due to medical malpractice, and can be potentially life-threatening.3

What are Gallstones?

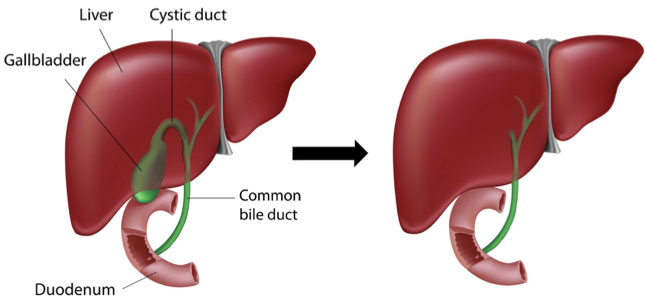

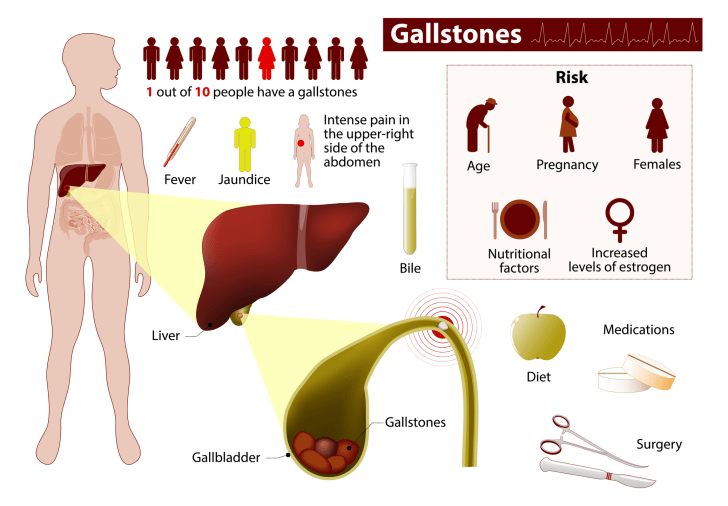

The gallbladder is a small sac-shaped organ situated beneath the liver; it stores bile which is secreted by the liver to help digestion. Sometimes bile can crystallize and form stones in the gallbladder or in the ducts that run to and from the gallbladder. These "gallstones" can be as small as a grain of salt or as large as a golf ball. When gallstones block the flow of bile out of the gallbladder, the gallbladder becomes swollen and inflamed. This can result in severe abdominal pain, usually on the right side. Even worse, this can result in infection, and other signs or symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, chills and fever. Some basic facts and statistics about gallstones are illustrated in this chart:

Credit: © Designua | Dreamstime.com

As seen in the chart, medication and diet may help some people to avoid further gallstone or gallbladder disease, but many people require some form of medical or surgical intervention for the problem. Lithotripsy (i.e. ultrasound focused shock-wave treatment) and/or bile acids can be used sometimes to break up the stones, but these medical treatments are not always successful, and some people are prone to reforming stones again. So, surgery to remove the gallbladder is a very common operation for this condition.

How is Gallbladder Removal Surgery Performed?

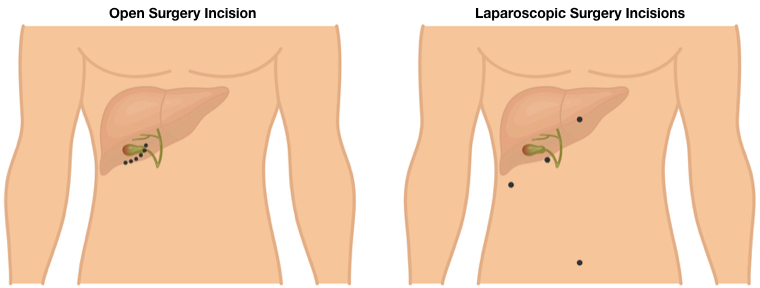

Gallbladder removal surgery can be performed either as an open procedure or, more commonly, with laparoscopy. The entry incision, or ports of surgical entry, are illustrated below.

Credit: © Masia8 | Dreamstime.com

Laparoscopic Gallbladder Removal (Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy)

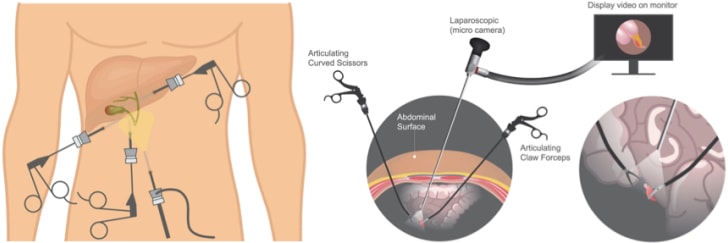

Laparoscopic gallbladder removal is one of the most common surgical procedures throughout the world.4 It is performed much more often than open surgery to remove the gallbladder because it offers smaller scarring, less discomfort, quicker recovery, and shorter hospital stays. But because laparoscopic gallbladder removal does not allow for "hands-on" surgery, the caveat is that while bile duct injuries are infrequent today, they are still 2-4 times more likely to occur with laparoscopic gallbladder removal than they are with open surgery to remove the gallbladder.5 Laparoscopic surgery to remove the gallbladder basically involves the insertion of: a needle or trocar to inflate the abdominal cavity for greater viewing space, a narrow tube with a camera (laparoscope) for the surgeon to see the patient's gallbladder on a monitor, and elongated instruments (e.g., cautery, scissors, forceps and graspers) for the procedure.

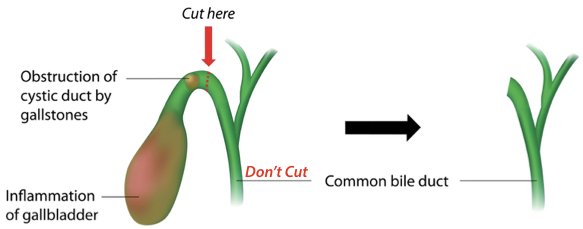

Among the numerous steps of the procedure, the surgeon has to dissect the cystic duct from the gallbladder to detach and remove it, while leaving the common bile duct intact and unharmed.

Credit: © Alila07 | Dreamstime.com

The Surgical Error of Cutting the Common Bile Duct

The most frequent reason for iatrogenic injury to the common bile duct in gallbladder removal surgery is that the surgeon misidentifies the common bile duct as the cystic duct.6 So, instead of cutting where he or she is supposed to, at the cystic duct, the surgeon instead cuts the common bile duct. To prevent this misidentification and medical malpractice, a critical examination of the gallbladder and duct anatomy must occur in surgery prior to critical dissection.7

As seen in a close-up view of this anatomy, the cystic duct must be cut above where it joins the common bile duct, not at or below the common bile duct.

Credit: © Alila07 | Dreamstime.com

Reasons for Misidentification of, and Injury to, the Common Bile Duct

There are well-reported reasons why surgeons inadvertently injure the common bile duct during gallbladder removal surgery. While the bile duct injury can occur as a result of surgeon malpractice due to poor surgical technique or technical factors,8 the injury occurs 70% - 80% of the time because the surgeon misidentifies the anatomy before clipping, cutting or suturing. Misidentification, in turn, is related to the surgeon's experience and skill, surgical exposure of the anatomy, and variations of the patient's anatomy. These things may all involve medical or surgical malpractice.9

Lack of Training and/or Experience

There is a known "learning curve" with laparoscopic surgery, and it has been reported that most injuries to the common bile duct occur within the first 13 of such procedures performed by a surgical resident or surgeon.10 Likewise, it has been estimated that the procedure needs to be performed about 15-20 times before he or she becomes proficient.11 Laparoscopic gallbladder surgery is unique: laparoscopic skills in one type of surgery, e.g. colon resection, do not necessarily transfer to another laparoscopy procedure, e.g. gallbladder removal.12 While laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been a standard part of U.S. surgery residents' training for around a quarter of a century, with surgery residents having typically performed over 50 laparoscopic gallbladder removal surgeries by graduation, some older or foreign-trained surgeons may nonetheless lack the training or experience to be proficient in laparoscopy cholecystectomy.13

Poor Operative Exposure

Sometimes the way the surgeon retracts the gallbladder can result in parallel alignment of the cystic and common bile ducts, thus creating the illusion that the cystic duct is the common bile duct, and vice versa. Likewise, operative bleeding, fat inside the abdomen, inflammation and/or scarring can obscure the surgeon's view or cause distortion of the anatomy. For these reasons, the surgeon has to ensure that he can adequately visualize the anatomy clearly before he proceeds to clamp or cut. In certain situations, difficult visualization may require the surgeon to convert to an open procedure rather than to risk cutting in the face of poor exposure.14

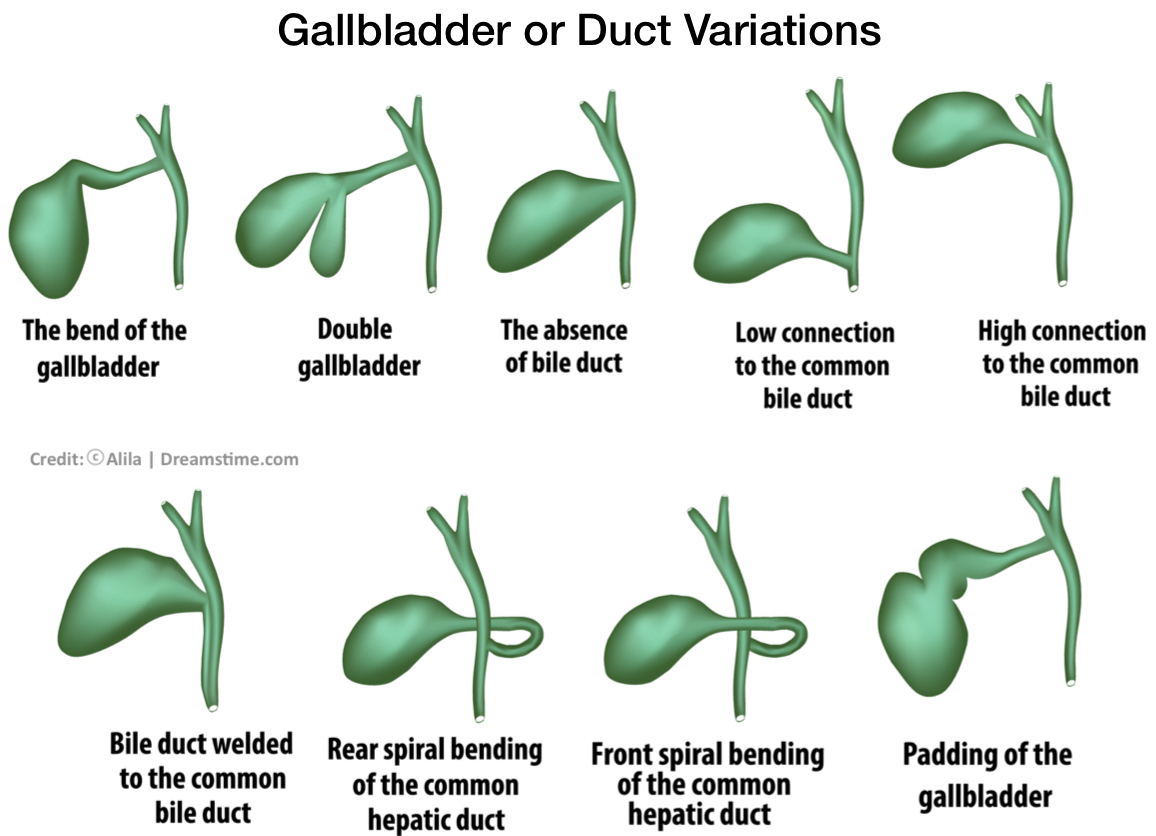

Variant Anatomy

Another reason for misidentification of the common bile duct is that some patients have aberrant or unusual anatomy of the biliary tract, i.e. gallbladder and ducts.

This may include variations such as a short or absent cystic duct, a cystic duct tethered to the common bile duct, or a cystic duct entering the nearby hepatic duct before joining the common bile duct. Accordingly, the surgeon has to be very careful to identify conclusively the ducts before he cuts. In cases where the anatomical variation creates doubt, intraoperative imaging (cholangiogram) with dye may be used to better visualize the ductal network, or the surgeon may need to obtain help from another or more experienced surgeon, before proceeding further.15

Life-Threatening or Life-Long Problems from Bile Duct Injury

Bile duct injuries are potentially devastating. They can lead to bile leaking in the abdominal cavity, severe infection, and narrowing (stricture) of the duct that can result in liver cirrhosis and failure. Consequently, bile duct injuries result in significant physical impairment and sometimes even death.16 Patients who have iatrogenic bile duct injuries from laparoscopic procedures normally have more severe injuries than those who are injured in open surgery, and prompt recognition of the injury (including with cholangiogram) is required so that surgical reconstruction of the biliary duct/tract can occur before the foregoing complications can develop.17 Unfortunately, up to 85% of the time such injuries are not immediately or promptly recognized.18 The patient who experiences bile duct injury will commonly experience yellowing of the skin (jaundice), fever, chills, and abdominal pain. The patient's condition of course worsens without timely recognition and proper repair of the injury. Since the necessary surgical reconstruction is usually complex, especially with severe bile duct injuries, specialized hepatobiliary surgeons and referral centers have been reported to give better patient outcomes.19 Nevertheless, even after bile duct reconstruction and repair a patient may still be left with significant and permanent gastrointestinal problems and may develop chronic problems like strictures or even life-threatening conditions such as bile duct infection (cholangitis), or an inflamed pancreas (pancreatitis).20

The Lawyer's Role

The lawyer who is experienced in handling gallbladder surgery malpractice and common bile duct injury cases will know and understand the anatomy, the surgery, and the authoritative medical literature on this subject. He or she will be able to work with qualified surgeons and other expert witnesses to determine how and why a common bile duct injury occurred, as well as if it was timely recognized and properly repaired.

Contact Us

The attorneys at Clore Law Group have significant experience and expertise with handling general surgery, gallbladder surgery, and common bile duct injury malpractice cases to successful resolution. We have handled such cases where patients have suffered iatrogenic bile duct injuries in open surgery and in laparoscopic procedures, including by surgeons in training, as well as by experienced surgeons; and we have successfully handled such cases where patients' bile duct injuries were not timely recognized, leading to severe infection, life-threatening complications, and severe, permanent injuries. If you think that you or a loved one may have experienced a tragic outcome like this from gallbladder surgery or other general surgery, you can email us at [email protected], or call us Toll-Free at 1-800-610-2546 for a free consultation.

Sources

- Jablonska B, Lampe P, Iatrogenic bile duct injuries: Etiology, diagnosis and management, World J. Gastroenterol. Vol. 15, No. 33, pp. 4097 – 4104, at 4097-98 (Sep. 7, 2009).

- Id. at 4097.

- Phillips EH, et al, Operative Strategies in Laparoscopic Surgery, Ch. 13 by Soper NJ and Strasberg SM, Avoiding and Classifying Common Bile Duct Injuries During Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy, at 65 (Springer 1995).

- Jabonska B, Lampe P, Iatrogenic bile duct injuries, n1, at 4097.

- Phillips EH, et al, Operative Strategies in Laparoscopic Surgery, Ch. 13 by Soper NJ and Strasberg SM, n3, at 65; Dziodzio T, Weiss S, et al, A critical view on a classical pitfall in laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Int J Surg Case Rep. Vol. 5, pp. 1218-21, at 1218 (2014).

- Jabonska B, Lampe P, Iatrogenic bile duct injuries, n1, at 4098; Strasberg SM, Brunt LM, Rationale and Use of the Critical View of Safety in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy, J Am Coll Surg. Vol. 211, No. 1, pp. 132-38, at 132 (2010); Dziodzio T, Weiss S, et al, A critical view on a classical pitfall in laparoscopic cholecystectomy, n5, at 1218.

- Strasberg SM, Brunt LM, Rationale and Use of the Critical View of Safety in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy, n6; Dziodzio T, Weiss S, et al, A critical view on a classical pitfall in laparoscopic cholecystectomy, n5, at 1218.

- Phillips EH, et al, Operative Strategies in Laparoscopic Surgery, Ch. 13 by Soper NJ and Strasberg SM, n3, at 66 (noting common bile duct injuries from failure to occlude the cystic duct, dissection performed too deeply, and cautery injuries); Jablonska B, Lampe P, Iatrogenic bile duct injuries, n1, at 4099 (noting injuries due to excessive dissection at the margins of the common bile duct during open procedures).

- Jablonska B, Lampe P, Iatrogenic bile duct injuries, n1, at 4098-99; Phillips EH, et al, Operative Strategies in Laparoscopic Surgery, Ch. 13 by Soper NJ and Strasberg SM, n3, at 66.

- Phillips EH, et al, Operative Strategies in Laparoscopic Surgery, Ch. 13 by Soper NJ and Strasberg SM, n3, at 66. See also Lekawa M, Shapiro SJ, et al, The laparoscopic learning curve, Surg Laparosc Endosc. Vol. 5, pp. 455-458 (1995); Sariego J, Spitzer L, et al, The "learning curve" in the performance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, J Int Surg. Vol. 78, pp. 1-3. (1993).

- Zucker KA, Bailey RW, et al, Laparoscopic guided cholecystectomy, Am J Surg. Vol. 161, pp. 36-42 (1991); The Southern Surgeons Club, A prospective analysis of 1518 laparoscopic cholecystectomies, N Engl J Med. Vol. 324, pp. 1073-1078 (1991); Moore MJ, Bennett CL, The Southern Surgeons Club, The learning curve for laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Am J Surg. Vol. 170, pp. 55-59 (1995); Gigot J, Etienne J, et al, The dramatic reality of biliary tract injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: An anonymous multicenter Belgian survey of 65 patients, Surg Endosc. Vol. 11, pp. 1171-1178 (1997).

- Grundfest WS, Credentialing in an era of change, JAMA. Vol. 270, p. 2725 (1993); Agachan F, Joo JS, et al, Intraoperative laparoscopic complications. Are we getting better? Dis Colon Rectum. Vol. 39, p. S14-19 (1996).

- Dent TL, Training and privileging for new procedures, Surg Clin North Am. Vol. 76, pp. 615-621 (1996); Parsa CJ, Organ CH, Jr., et al, Changing patterns of resident operative experience from 1990 to 1997, Arch Surg. Vol. 135, pp. 570-73 (2000).

- Phillips EH, et al, Operative Strategies in Laparoscopic Surgery, Ch. 13 by Soper NJ and Strasberg SM, n3, at 66; Malik AM, Laghari AA, Iatrogenic biliary injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, A continuing threat, Int J Surg. Vol. 6, pp. 392-95, at 394 (2008). See also Prevention & Management of Laparoscopic Surgical Complications, The 1st Edition, Ch. 8 by Shayani V, Jacobs L, et al, Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy II, Soc of Laparoscop Surg., Operative Procedure, at: https://laparoscopy.blogs.com/prevention_management/2006/01/chapter_8_lapar.html.

- Id.

- Thompson CM, Saad NE, Management of Iatrogenic Bile Duct Injuries: Role of the Interventional Radiologist, Vasc/Interven Radiol. Radiographics, pp. 117-134, at 117-18 (RSNA 2013); Dziodzio T, Weiss S, et al, A critical view on a classical pitfall in laparoscopic cholecystectomy, n5, at 1220 (noting short-term mortality of 1.9%).

- See, e.g., Slater K, Strong RW, et al, Iatrogenic bile duct injury: the scourge of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, ANZ J Surg. Vol. 72, No. 2, pp. 83-88 (Feb. 2002); Jablonska B, Lampe P, Iatrogenic bile duct injuries, n1, at 4097.

- Jablonska B, Lampe P, Iatrogenic bile duct injuries, n1, at 4099; Slater K, Strong RW, et al, Iatrogenic bile duct injury: the scourge of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, at 83; Carroll BJ, Birth M, Common bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy that result in litigation, Surg Endosc. Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 310-314 (Apr. 1998).

- Salama IA, Shoreem HA, Iatrogenic Biliary Injuries: Multidisciplinary Management in a Major Tertiary Referral Center, HPB Surg. pp. 1-12, at 1 (Nov. 10, 2014); Flum DR, Cheadle A, et al, Bile Duct Injury During Cholecystectomy and Survival in Medicare Beneficiaries, JAMA Vol. 290, No. 16, pp. 2168-73 (Oct. 22-29, 2003).

- AbdelRafee A, El-Shobari M, et al, Long-term follow-up of 120 patients after hepaticojejunostomy for treatment of post-cholecystectomy bile duct injuries: A retrospective cohort study, Int J Surg. pp. 205-10 (Jun. 18, 2015).