Airway Medical Malpractice—Part III of III: Failure to Rescue the Patient in an Emergency

It has been said that the difficult airway is something practitioners should anticipate and plan for, but that the failed airway is something they experience.1 While there really isn't a disconnect between these situations--because the former can lead to the latter as discussed in Parts I and II of this series on airway medical malpractice--the skills necessary to rescue a patient with a failed airway are something that anesthesia and emergency medicine providers are taught, that they undergo simulations, practice and training for, and that they have the responsibility to apply when they cause it or encounter it.

In Emergency Medicine circles, a "failed airway" is seen when the practitioner (1) cannot intubate but can oxygenate (with a face-mask), or (2) cannot intubate and cannot oxygenate (CICO), after failed laryngoscopy or failed intubation.2 If the first scenario occurs, then the emergency caregiver has time to evaluate and attempt to execute other intubation options3 but, in the event of the second situation, an emergency approach must be taken. While healthcare providers normally refer to these situations as the (1) non-emergency pathway or (2) the emergency ("cannot intubate, cannot ventilate"(CICV)) pathway, these acronyms essentially mean the same thing, and the rules for all practitioners (regardless of specialty) are substantially the same. The failure to follow the rules can amount to medical malpractice. 4

The Emergency Failed Airway Situation

Thankfully, the CICV emergency is uncommon in the operating room (OR); it is estimated to occur only in 1/5,000 to 1/20,000 intubations,5 but most busy hospitals are estimated to have several such patient-events each year.6 For emergency caregivers outside the OR, the true incidence of CICO is unknown but is probably much more common because of the urgency of these patients,7 and the numerous conditions that are more often encountered that result in a closed airway--e.g. neck trauma, airway swelling (anaphylaxis or allergy-related), obstruction from inhaled foreign objects/choking, etc. It is known, however, that rescue surgical airways occur in anywhere from 1/50 to 1/200 patients where intubation was unsuccessful, including in emergency departments.8

Last Chance for Emergency Non-Surgical Intervention

When there is a CICO or CICV emergency, the algorithm rules from both emergency medicine experts and the American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) basically allow the practitioner a final opportunity to try a supraglottic or extraglottic device.9 (See part II of this series). If that does not work, however, the practitioner is forced to go to an emergency surgical airway alternative,10 as time is critical and delay can rapidly be followed by brain injury or death. Excessive delay can constitute medical malpractice.11

The Surgical Airway Rescue

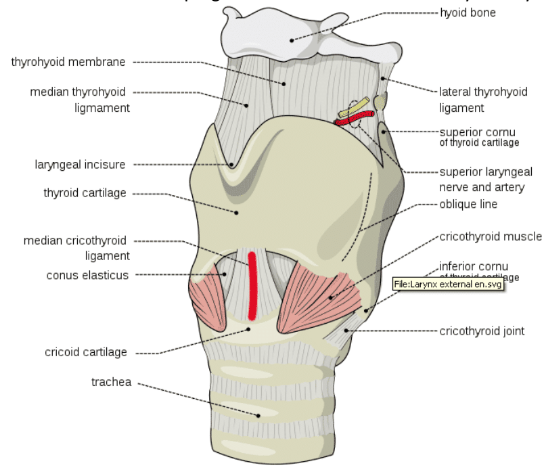

Leading authorities in emergency medicine recommend a cricothyrotomy (see illustration right) as the primary procedure for the CICO situation where a supraglottic device fails.12 A cricothyrotomy involves a surgical (or needle) opening made through the skin and cricothyroid membrane into the trachea, where a small tube is inserted in order to allow air to go into the windpipe.

(See anatomical model photo) Credit: 117811812 © | Dreamstime.

There are, however, certain conditions that make a cricothyrotomy difficult or impossible to achieve. To assess this possibility rapidly in order to determine if an alternative surgical airway procedure should be used, emergency medicine experts recommend the pneumonic aid "SMART,"13 which stands for:

Surgery: scarring from past surgery in or around the airway or throat, can distort the airway anatomy, may complicate the cricothyrotomy.

Mass: confined blood in the airway can make the procedure more difficult as well.

Access/Anatomy: infection in the tissues of the neck or throat, obesity, and surgical collars can also hinder surgical access.

Radiation: past exposure can also result in scarring and distortion of the airway anatomy.

Tumor: a mass in the airway can also make access more difficult, and bleeding worse.

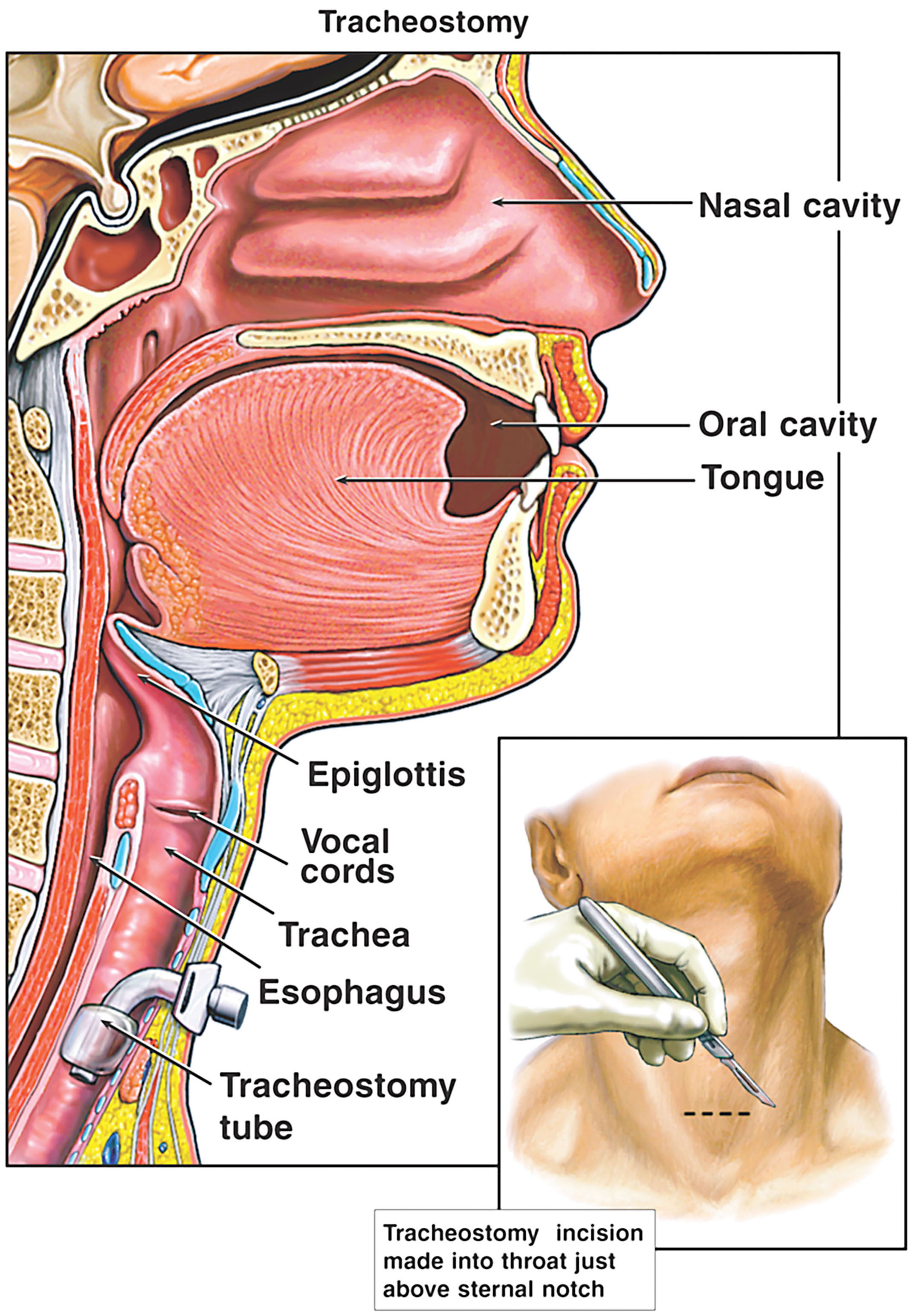

Cricothyrotomy, when appropriate, is fairly straightforward and can be accomplished with a high rate of success and low rate of complications by emergency practitioners who have adequate training.14 This emergency surgical option is generally regarded as easier and quicker than a tracheostomy (see illustration below right), and can be used by emergency caregivers, as well as anesthesia providers according to the ASA.15 The ASA also states that other surgical methods or techniques can be used as well. 16

Who Knows How to Do It?

The caveat, however, is basic competence. This dilemma is a recognized problem in emergency medicine, as commentators have noted:

"Most clinicians who are responsible for airway management have either limited or no experience with these procedures. Whether in the prehospital setting, the emergency department, the operating room, the inpatient unit, or the intensive care unit, surgical airway management is simply not required very often. . . ."17

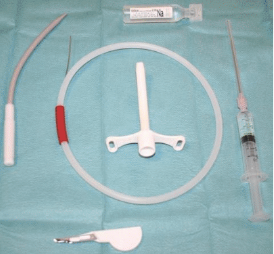

This problem is not unique to emergency practitioners, as less than half of all anesthesiologists also believe they are competent to perform a cricothyrotomy.18 For these reasons, there are various cricothyrotomy "kits" (see example photo below, left) with needles, syringes, equipment and instructions that are commercially available that are designed to make the procedure easier and/or safer to perform.

Credit: Svenriviere, Wikipedia, Cricothyrotomy Kit, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Once again, however, studies have shown that safety and success with these specialized kits and techniques depends on operator experience, and that the standard cricothyrotomy procedure may work better for both emergency and anesthesia caregivers with limited expertise.19

When and How Is it Done to Avoid Medical Malpractice?

Even though the practitioner may have limited experience with a surgical airway, the risks of performing it, or delaying the performance of it, must be weighed against the certainty that the CICO patient will soon suffer brain injury or death without it. In this regard, the lack of oxygen and/or build-up of carbon dioxide in the body may have already reached a level where minutes or even seconds remain to avoid disaster.20 While the overall incidence of these disasters may be decreasing,21 they remain a preventable outcome with proper care. Practitioners in these circumstances may be negligent and commit medical malpractice if they: fail to attempt the surgical airway, or do not to attempt it until it is already too late, or when they don't know how to perform a surgical airway with basic competence.

The Lawyer's Role

The lawyer who is experienced in prosecuting medical malpractice cases involving airway intubation and ventilation deviations will know and understand these concepts, the anatomy, the need for the surgical airway, and important literature on these subjects. He or she will be able to work with qualified emergency and anesthesiology practitioners, and other expert witnesses to determine if and when a surgical airway was required, as well as whether the tragic outcome of brain injury or death could have been avoided with a proper and timely surgical rescue.

Contact Us

The attorneys at Clore Law Group have extensive experience and expertise with handling airway-related medical malpractice cases to successful resolution. This includes cases against various healthcare practitioners responsible for intubation, mask ventilation, and the emergency or surgical airway. If you think that you or a loved one may have experienced a tragic outcome like this from improper care, you can email us at [email protected], or call us Toll-Free at 1-800-610-2546 for a free and confidential consultation.

Sources

- Walls RM, Murphy MF, Manual of Emergency Airway Management, p. 9 (4th ed. 2012).

- Brown CA, Sakles, JC, et al, The Walls Manual of Emergency Airway Management, Ch. 2, Identification of the Difficult and Failed Airway, by Brown CA & Walls RM, pp. 38-39 (Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins 5th ed. 2017). See also Part II of this series on Airway Medical Disasters.

- Id. Ch. 3, The Emergency Airway Algorithms, by Brown CA & Walls RM, at the Failed Airway Algorithm Fig 3-5, at 77-78 (revealing other options such as video laryngoscopy, use of an extraglottic device, etc.).

- Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway: An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway, Anesthesiol. Vol. 118, No. 2, pp. 251-70, at 257 (2013).

- Brown CA, Sakles, JC, et al, The Walls Manual of Emergency Airway Management, n2, Ch. 2, at 37-38.

- See Hagberg CA, Hagberg and Benumoff's Airway Management, Ch. 8, Definition and Incidence of the Difficult Airway, by Klock PA, p. 182 (4th ed. Mosby 2018).

- Id.

- Id.; Gibbs MA, Mick NW, Ch. 31, Surgical Airway (Feb. 27, 2015), Part 1 Introduction, found at: https://clinicalgate.com/surgical-airway/.

- Brown CA, Sakles, JC, et al, The Walls Manual of Emergency Airway Management, n2, Ch. 3, The Emergency Airway Algorithms, by Brown CA & Walls RM, at the Failed Airway Algorithm Fig 3-5, at 77-78; ASA Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway, n4, at 257.

- Id.

- Id.; Gibbs MA, Mick NW, n8, Ch. 31, Surgical Airway, III, Surgical Cricothyrotomy; Brown CA, Sakles, JC, et al, The Walls Manual of Emergency Airway Management, n2, Ch. 3, The Emergency Airway Algorithms, by Brown CA & Walls RM, at the Failed Airway Algorithm, at 77-78.

- Id. at Fig. 3-5.

- Id., Ch. 2, at 53-55.

- Gibbs MA, Mick NW, Ch. 31, Surgical Airway, at Part 1B, Historical Perspective, at: https://clinicalgate.com/surgical-airway/.

- ASA Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway Algorithm, n4, at 257. Note that tracheostomy may be harder for non-surgical practitioners to perform, see, e.g, Spiegel JE, Shah V, Surgical Management of the Failed Airway, A Guide to Percutaneous Cricothyrotomy, Anesth. News 2014, pp. 47-51, at 51, and it is considered a longer and more invasive procedure that surgeons are more comfortable with. Haymans F, Feigl G, Emergency Cricothyrotomy Performed by Surgical Airway-Naive Medical Personnel, Anesthesiol. Vol. 125, No. 2, pp. 295-303, at 295 (Aug. 2016).

- ASA Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway, n4, at 257, Fig. 1(b)(also referencing jet ventilation and retrograde intubation).

- Gibbs MA, Mick NW, Ch. 31, Surgical Airway, n8, Part 1 Introduction.

- Brambrink AM, Hagberg, CA, The ASA Difficult Airway Algorithm, Ch. 10, sec. E, The "Cannot Intubate, Cannot Ventilate" Scenario (Feb. 27, 2015), at: https://clinicalgate.com/the-asa-difficult-airway-algorithm-analysis-and-presentation-of-a-new-algorithm/#s0030.

- Helm M, Emergency cricothyroidotomy performed by inexperienced clinicians‚ surgical technique versus indicator-guided puncture technique, Emer J Med. Vol. 30, No. 8, pp. 646-49 (Jul 27, 2012); Haymans F, Feigl G, Emergency Cricothyrotomy Performed by Surgical Airway Medical Personnel, n15, at 295.

- Brambrink AM, Hagberg, CA, The ASA Difficult Airway Algorithm, n18, at E, The "Cannot Intubate, Cannot Ventilate" Scenario; Brown CA, Sakles, JC, et al, The Walls Manual of Emergency Airway Management, n2, Ch. 3, The Emergency Airway Algorithms, by Brown CA & Walls RM, at 77-78.

- Hagberg CA, Hagberg and Benumoff's Airway Management, n 6, Ch. 8, Definition and Incidence of the Difficult Airway, by Klock PA, at 182.