Airway Medical Malpractice—Part II of III: Failure to React to the Difficult Airway

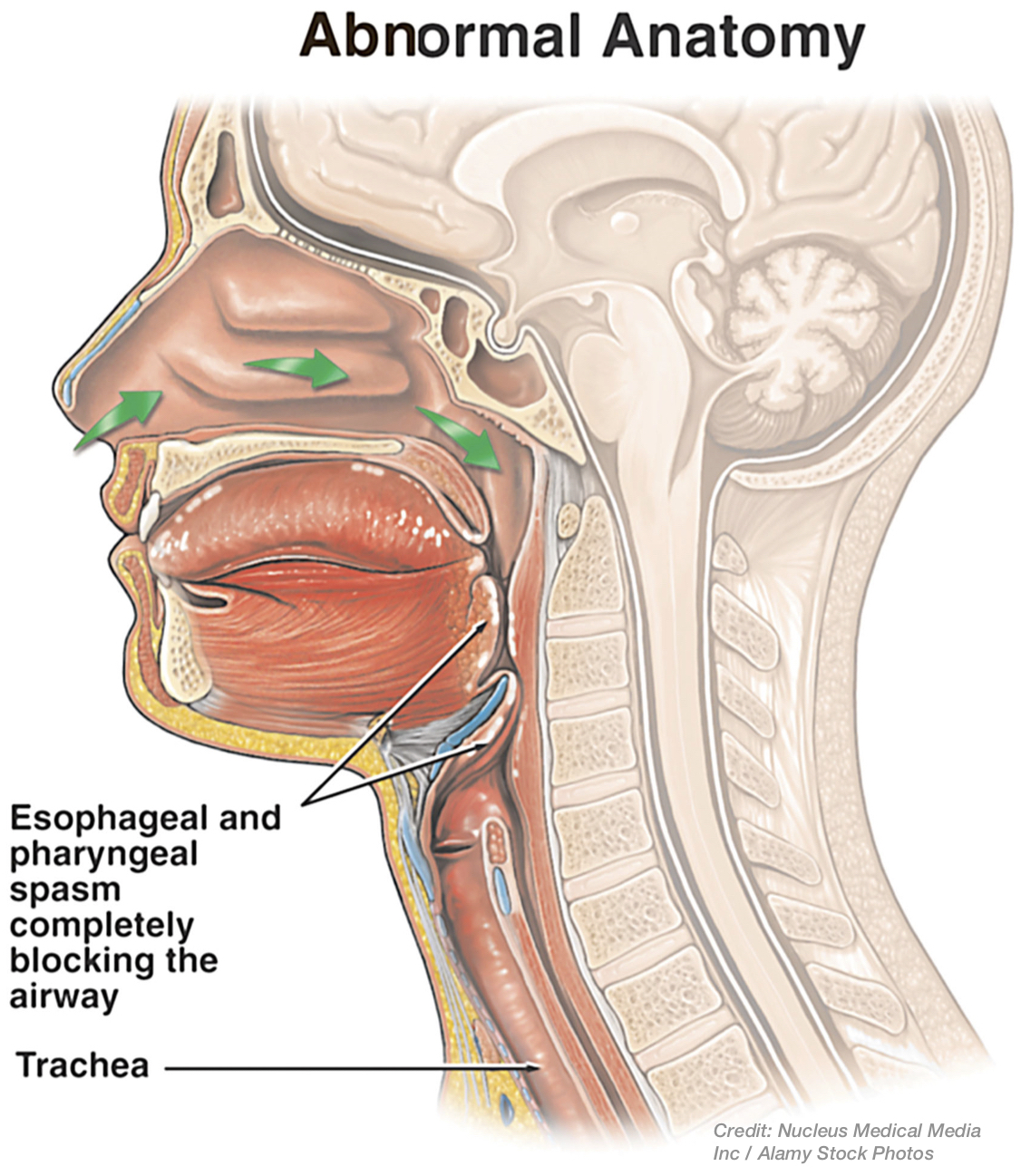

Einstein is commonly credited with saying that the definition of insanity means "doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting different results."1 In part I of this series on airway medical malpractice, we pointed out that repeated laryngoscopy or intubation attempts can result in a critically dangerous situation (where brain damage can occur within minutes) if the health care provider cannot intubate and cannot ventilate the patient. This is because the structures in and around the voice box area (larynx) are so delicate. These structures can be lacerated or damaged with continued attempts at laryngoscopy or tracheal intubation, and this can cause bleeding, swelling, spasm and thus obstruction of the airway.2 So, airway experts warn against trying the same intubation technique again when it did not work before.3

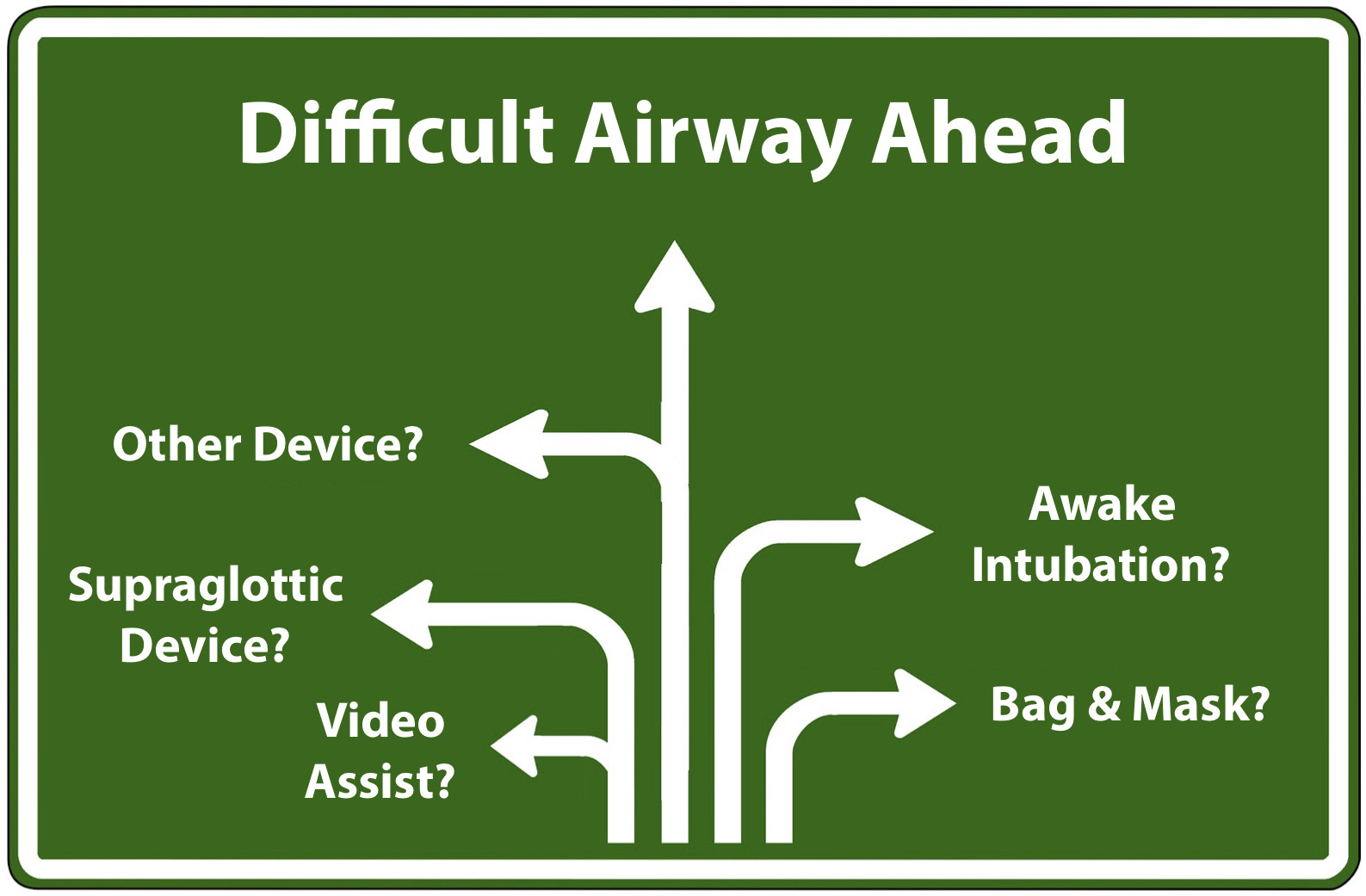

The way the practitioner reacts to a difficult intubation or difficult airway is very important. If the difficult intubation or airway is anticipated, then the practitioner can respond ahead of time by planning and having a strategy for the situation, including different intubation techniques, options and/or using advanced or specialized airway equipment. This will hopefully avoid the danger but, if the difficult airway is not anticipated, then the time to react may be more limited, and how the practitioner reacts is critical. The failure to react timely and properly to the difficult airway can amount to medical malpractice.

To make matters worse, it is well-known that increased intubation difficulty occurs when practitioners are not skilled or well-experienced in intubation,4 and that airway disasters are often associated with misuse of airway equipment due lack of knowledge or training, as well as improper reaction to the patient or the situation, including from: task fixation, poor awareness and communication, poor leadership and team-work, and failure to follow recommendations and standard guidelines. These things can also constitute medical malpractice.5

Reacting to Anticipated Airway Difficulty

Before intubation is accomplished, practitioners usually give the patient a sedative and/or hypnotic drug followed by a paralytic drug. This facilitates the laryngoscopy and intubation. But when the patient has a difficult airway, the point at which the practitioner may lose control to be able to rescue the patient quickly from breathing problems is when the anesthetic/paralytic is given. The reason is that even if the practitioner encounters problems and needs to wake the patient up, or reverse the drug(s), to breathe, it can take around 10 minutes or so to do this; and, in the meantime if the patient is without oxygen for this long he or she can still suffer brain injury or death.6

So, when airway difficulty is anticipated, there are various guidelines and rules for practitioners to follow to avoid this situation, and so as not to make a difficult airway an impossible one in which to ventilate the patient.

Anesthesia Providers – anesthesiologists, their assistants, CRNA's

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) has a "Difficult Airway Algorithm"7 that contains statements and diagrams of recommendations and steps for anesthesia providers to follow in patients with difficult airways, both when anticipated and not anticipated, including in terms of intubation, facemask ventilation, and/or airway emergencies. The algorithm applies to intubations both when the patient is awake, and those after the patient has received a general anesthetic.

When a difficult airway is anticipated before surgery in the patient who is conscious, the ASA recommends strategies and measures be considered to reduce the incidence of failed intubation. This includes pre-oxygenation of the patient, and techniques to perform an "awake" intubation if appropriate, including with oral topical anesthesia, via a nasal or oral route, and/or with camera and flexible scope assisted equipment (i.e. video laryngoscopy‚ see photo left).8 Properly executed awake intubation has a high degree of success, and video-assisted intubation has a higher frequency of success as well.

Further, the pre-oxygenation and monitoring in this setting often reveals before intubation if there will be difficult mask ventilation.9 In short, avoiding general anesthesia with awake intubation avoids the significant potential for harm in these patients. There are two general situations, however, in which an anesthesiologist will still be required to perform intubation of the trachea of an unconscious or anesthetized patient despite anticipation of a difficult intubation or airway: (1) in certain patients who are already unconscious (i.e., post-trauma) or anesthetized (i.e.., drug overdose), since these conditions make intubation more difficult; and, (2) in patients who absolutely refuse or cannot tolerate awake intubation (e.g., children, a mentally handicapped patient, critically ill or an intoxicated patient.).10 In these situations where awake intubation is not possible, the anesthesia provider should identify whether or not the patient will likely be difficult to ventilate, and should have a strategy as to how and what advanced intubation equipment should be utilized to provide greater odds of successful intubation. In this regard, there are many different types of advanced airway devices that can be utilized in cases of the difficult airway.11 Two of the more common advanced devices include the above video-assisted laryngoscopy, or the use of an airway device that is more easily inserted to, but not beyond, the glottis, i.e. a supraglottic device (see Supraglottic Airway below). And the anesthesia provider is encouraged to monitor the patient's carbon dioxide levels (i.e. end-tidal CO2 monitoring) to ensure ventilation.12

Emergency Medical Providers – ED doctors, EMTs/paramedics, others

There are also nationally recognized algorithms for emergency physicians to follow with the difficult airway.13 When emergency physicians encounter the suspected difficult airway, they likewise should determine if mask ventilation will likely be difficult or not. The pneumonic, "ROMAN," is recommended by experts to do so,14 standing for:

- Radiation/Restriction: prior radiation treatment to the neck, or airway/lung restrictions with conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) make ventilation difficult.

- Obesity/Obstruction: both conditions can make ventilation difficult.

- Mask seal/Male/Mallampati: beards, blood or facial debris, male gender, and limited visibility of throat structures inside the mouth are all indicators that bag and mask ventilation may be difficult to achieve.

- Age: patients over age 55-57 may be more difficult to ventilate due to less muscle tone in the upper airway.

- No teeth: may make it difficult for the bag seal to stay formed to the face.

If the emergency physician is forced to act and intubate, rather than to mask ventilate the patient, he or she is encouraged to perform a rapid sequence intubation, using the one best (continuous) attempt with laryngoscopy to insert the ET tube.15 On the other hand, if bag and mask ventilation can be maintained, the emergency practitioner may have options to consider awake intubation, or to use advanced airway equipment, including either video or camera-assisted devices (see photo right) or a supraglottic device (see below), if needed.16

It should also be noted that other emergency practitioners such as paramedics and EMS providers often have algorithms or standard operating procedures (SOPs) to follow for the difficult airway, but those rules or SOPs vary widely across the country depending on, for example, the type of airway equipment the emergency practitioner carries or has available.17

Credit: Right Photo from Endotracheal intubation with a video-assisted semi-rigid fiberoptic stylet by prehospital providers, by Cooney DR, Beaudette C, Clemency BM, Tanski C, Wojcik S, Int J Emerg Med., Fig 2 (2014); license & disclaimer at (CC BY 4.0).

Reacting to Airway Difficulty that was Unanticipated

Regular endotracheal intubation of the difficult airway, without advanced equipment, may also occur because the airway was difficult to predict or, perhaps more commonly, because the practitioner failed to recognize the likely intubation difficulty upon direct laryngoscopy or at the pre-anesthesia evaluation, as the case may be.18

Anesthesia Providers – anesthesiologists, their assistants, CRNA's

The ASA algorithm for intubation after a general anesthetic is given discusses what the anesthesia provider should consider after attempts at initial intubation have failed. A significant point made in the algorithm is that the first solution for the anesthesia provider may simply be calling for help and cancelling the medical or surgical procedure, maintaining facemask ventilation, and giving medication to wake the patient up to allow for normal breathing again. This practice makes sense at times for elective medical procedures, rather than having continual intubation failures, but sometimes the surgery cannot be aborted or rescheduled or, as previously mentioned, the counter-acting anesthesia drug(s) may take longer to awaken or un-paralyze the patient than he or she has time for so as to resume normal breathing.19

Difficult Mask Ventilation

In these circumstances, there are alternative intubation approaches to consider so long as the bag-and-mask ventilation is okay in the meantime. Difficulties with face-mask ventilation may be encountered though because of: the need for two hands to provide it, hand fatigue/cramping requiring different operators, and facemask seal leaks, all of which can make the ventilation inadequate in addition to the anatomical source causing the difficult intubation in the first place--e.g. usually a lack of airway patency, or obstruction or spasm at the voice-box or below it.20

The Supraglottic Airway

If facemask ventilation is not adequate after failed intubation, then the next step in the ASA algorithm is for the practitioner to consider using a supraglottic airway (SGA), which allows for the airway device to be inserted through the mouth to sit on top of the larynx (glottis). Most SGAs are cuff-like devices connected to an air tube, and the cuff is inflated to hold it in place once it reaches the desired position. The most common of such devices are laryngeal mask airways (LMA‚ seen in left photo) or intubating LMAs. The advantages to these devices include: easy insertion and use, not needing a precise placement, and less laryngeal trauma. These SGAs are routinely used at the start of many general anesthetic surgeries in anticipation of a difficult airway. The disadvantages are that the risk of aspiration may be greater than with an ET tube, and that the patient's airway obstruction may be below the glottis, so that the SGA is ineffective at ventilation.21

Emergency Medical Providers -- ER doctors, EMTs/paramedics, others

Emergency medical practitioners are presented with a much different situation, of course, in that they are not dealing with elective procedures or situations. For emergency practitioners, the supraglottic (also known as extraglottic) airway device (EGD) may be a first line choice for airway rescue, in lieu of endotracheal intubation.22

In addition to the LMA seen above, another device often used by pre-hospital emergency providers is the Combitube (see photo examples on right), which can also be inserted without performing laryngoscopy. Once again, the emergency practitioner is advised to use a rapid screening pneumonic aid ("RODS") to predict whether the extraglottic device will be successful. The letters stand for:

- Restricted Mouth Opening: an adequate-sized mouth opening is needed for an EGD.

- Obstruction/Obesity: if something is blocking the airway at the level of the glottis or below, then an EGD (placed above the glottis) may not be able to get air through to the lungs.

- Disrupted/Distorted Airway: is there any injury to the patient's body that would impede the device, such as abnormality of the neck, bleeding in the airway, etc.

- Stiff: again, ventilation may be more difficult in these patients.

Avoiding Medical Malpractice

The purpose of algorithms, pneumonic aids, and SOPs in the setting of the difficult airway is self-evident: for practitioners to avoid making the anticipated difficult airway worse, and to react timely and properly to it when it is unsuspected. Time is of the essence, and a cannot-intubate-or-ventilate situation is an emergency. This situation should be avoided whenever possible, and there are options for the practitioner to do so before anesthesia is given, after anesthesia/paralytics but before the start of intubation, and after failed intubation attempt(s). Repetitive attempts at intubation after the best intubation attempt(s) can: cause airway bleeding, swelling, and airway spasm, make the intubation impossible to achieve, and prevent mask ventilation from being effective or adequate. And when this happens, an emergency surgical pathway must be quickly followed, as will be discussed in Part III of this 3 part series on airway medical malpractice.

From the lawyer's perspective, the following basic questions are commonly at issue in difficult airway medical malpractice cases, and some of the dangers can be summarized in these corresponding rhymes:

Was there a need to intubate?

If the practitioner's assessment revealed airway concern, did he know that an anesthetic or paralytic could cross the point of no return?

Was there an ability to effectively mask ventilate?

Did the practitioner consider the limitations of relying totally on mask ventilations?

What was the plan for the anticipated airway difficulty?

If the best intubation attempt(s) did not succeed, did the practitioner recognize that repetitive attempts could make the airway bleed?

What alternative airway device(s) were used?

Did the practitioner follow sound advice by attempting to insert a supraglottic device?

Was there a plan for the unsuspected difficult airway?

If there was any doubt, did the practitioner carry the appropriate algorithm or SOP out?

The Lawyer's Role

The lawyer who is experienced in prosecuting medical malpractice cases involving airway intubation and ventilation deviations will know and understand the medical concepts, the anatomy, the nature of the airway devices, and important literature on these subjects. He or she will be able to work with qualified expert witnesses in various fields related to airway medicine to determine if the practitioner reacted timely and properly to the difficult airway, or was negligent in doing so, as well as to analyze what went wrong and why that resulted in the tragic outcome of brain injury or death.

Contact Us

The attorneys at Clore Law Group have extensive experience and expertise with handling airway-related medical malpractice cases to successful resolution. This includes cases against various healthcare practitioners responsible for intubation, mask ventilation, and the emergency or surgical airway. If you think that you or a loved one may have experienced a tragic outcome like this from improper care, you can email us at [email protected], or call us Toll-Free at 1-800-610-2546 for a free and confidential consultation.

Sources

- See, e.g., https://www.quora.com/Did-Einstein-really-define-insanity-as-doing-the-same-thing-over-and-over-again-and-expecting-different-results.

- See, e.g., Laryngeal complications by orotracheal intubation: Literature review, Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 236-45 (2012); Eastman AL, Rosenbaum DH, et al, Parkland Trauma Handbook, Ch. 20 Neck Injuries, by McDougal J, pp. 157-64 (3rd ed. 2009); Redish CH, Laryngeal spasm: Causes, prevention and Treatment, Oral Surg, Oral Med, Oral Path., Vol. 8, No. 11, pp. 1139-45 (Nov. 1955).

- See, e.g., Brambrink AM, Hagberg, CA, The ASA Difficult Airway Algorithm, Ch. 10, sec. D, Difficult Intubation in the Unconscious or Anesthetized Patient, (Feb. 27, 2015), at: https://clinicalgate.com/the-asa-difficult-airway-algorithm-analysis-and-presentation-of-a-new-algorithm/#s0030 (pointing out that the swelling and bleeding in the larynx (voice box) area increases with every attempt when the laryngoscope blade is used, and that failed intubation attempts causing this condition lead to difficulty in ventilation, which is the most common scenario in "respiratory catastrophes.").

- See Hagberg CA, Hagberg and Benumoff's Airway Management, Ch. 8, Definition and Incidence of the Difficult Airway, by Klock PA, pp. 181 (4th ed. Mosby 2018). See also Walls RM, Management of the Difficult Error in the Trauma Patient, Emerg Med Clin of N Amer. Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 45-61 (1998); Butler KH, Clyne B, et al, Emergency Management of the Difficult Airway: New Techniques, Devices, and Interventional Approaches, Pt. 2 (Dec. 31, 2000); Taboada M, Doldan, P, et al, Comparison of Tracheal Intubation Conditions in Operating Room and Intensive Care Unit: A Prospective, Observational Study, Anesthesiol. Vol. 129, No. 2, pp. 321-28 (Aug. 2018); Brown CA, Sakles, JC, et al, The Walls Manual of Emergency Airway Management, Ch. 3, The Emergency Airway Algorithms, by Brown CA & Walls RM, pp. 75-76, at Fig. 3-4, Difficult Airway Algorithm (Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins 5th ed. 2017)(noting at key question 4 that, in the case of a failed airway, "persistent, futile attempts at intubation will waste critical seconds or minutes and may sharply reduce the time remaining for a rescue technique to be successful before brain injury ensues.").

- Management of the Difficult Airway, Ch. 22, (Feb. 27, 2015), sec. "Training, Teamwork and Human Factors," found at: https://clinicalgate.com/management-of-the-difficult-airway-2/.

- Id. at sec. "Securing the Airway Awake."

- Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway: An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway, Anesthesiol. Vol. 118, No. 2, pp. 251-70 (2013).

- Id. at 254-56.

- Id.; Management of the Difficult Airway, n5, at sec. "Difficult Mask Ventilation."

- See, e.g., Brambrink AM, Hagberg, CA, The ASA Difficult Airway Algorithm, n3, at sec. D.

- Id. at secs. C-D, Boxes 10-2 & 10-3.

- Id.; ASA Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway, n7, at 255-56.

- The Walls Manual of Emergency Airway Management, n4, Ch. 3, The Emergency Airway Algorithms, at 75-76, Fig. 3-4, Difficult Airway Algorithm.

- Id. at Ch. 2, Identification of the Difficult and Failed Airway, at 49-52, sec. Difficult BMV: ROMAN.

- Id. at Ch. 3, The Emergency Airway Algorithms, at 75-76 (referring to the critical action of performing rapid sequence intubation, such that one laryngoscopy maneuver is used even though multiple attempts to insert the ET tube may occur therein). Cf. ASA Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway, n7, at 257 (algorithm noting "attempts" at intubation).

- The Walls Manual of Emergency Airway Management, n4, Ch. 3, at 75-76, Fig. 3-4.

- White, D, Insights on Innovation: Managing the difficult airway in EMS (May 14, 2012), available at: https://www.ems1.com/ems-products/medical-equipment/airway-management/articles/1286439-Managing-the-difficult-airway-in-EMS/; EMSWorld, Are You Prepared for the Difficult Airway (Jan. 2005), which can be accessed at: http://emsairwayclinic.fireemsblogs.com/2011/07/14/airway-algorithms/.

- Brambrink AM, Hagberg, CA, The ASA Difficult Airway Algorithm, n3, Ch. 10, at sec. D.

- See, e.g., Management of the Difficult Airway, n5, Ch. 22, secs. "Securing the Airway Awake," and "Administration of Muscle Relaxants in the Patient with a Difficult Airway."

- See Hagberg CA, Hagberg and Benumoff's Airway Management, n4, Ch. 8, Definition and Incidence of the Difficult Airway, by Klock PA, at 178-80.

- Brambrink AM, Hagberg, CA, The ASA Difficult Airway Algorithm, n3, at sec. E "The Cannot Intubate, Cannot Ventilate" Scenario. See also Benumoff JL, Laryngeal Mask Airway and the ASA Difficult Airway Algorithm, Anesthesiol. Vol. 84, No. 3, pp. 686-89, at 688 (Mar. 1996).

- The Walls Manual of Emergency Airway Management, n4, Ch. 2, at 53-54, § "Difficult EGD: RODS."